Dr Cillian McBride

Senior Lecturer in Political Theory

23/06/2020

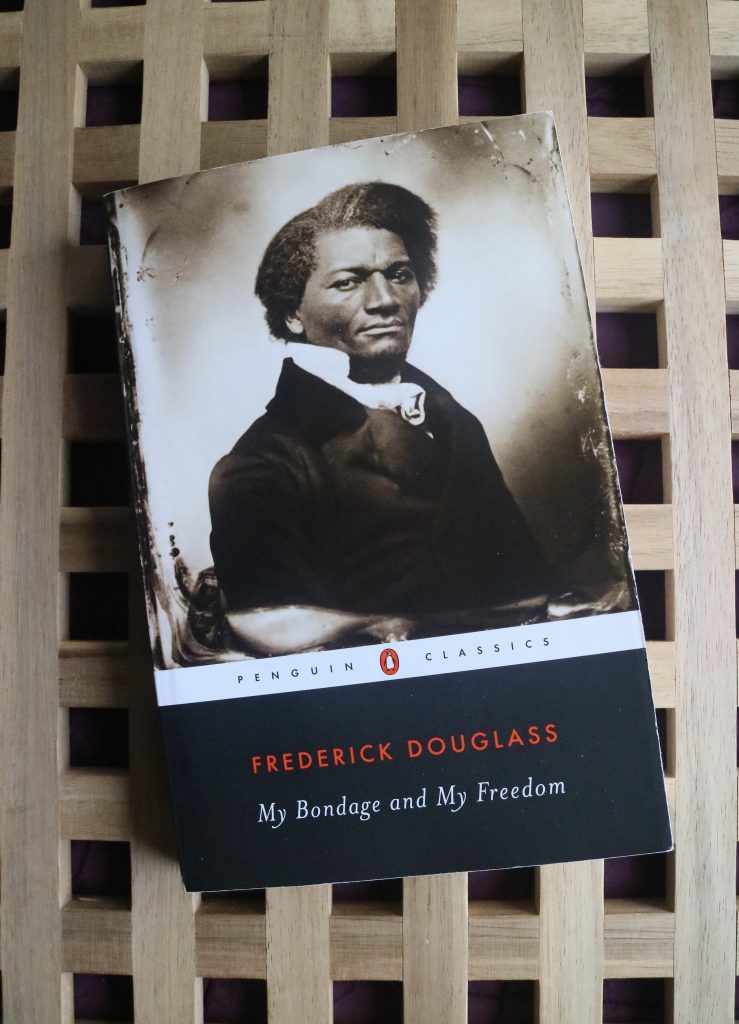

‘The first work of slavery is to mar and deface those characteristics of its victims which distinguish men from things, and persons from property’. These are the words of Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery in Maryland to become a leading campaigner for the abolition of slavery and for the rights of Black people. Besides his work as a public speaker, journalist and newspaper editor, Douglass also wrote a biography – publishing three versions of it in his lifetime – reflecting on his life in slavery and his subsequent emancipation, of which My Bondage and My Freedom was the second version.

I became interested in the experiences of figures like Douglass and his contemporary, Booker T. Washington, former slave and noted educationalist, when researching questions of recognition and respect. I was especially interested is the way in which people subject to the most extremely harsh and degrading treatment could nonetheless retain their self-respect in such conditions. While others were unable to resist the relentless humiliations heaped on them by their captors, some people nevertheless managed to hold onto their sense that they were entitled to be treated as equals. Primo Levi, writing about his own experiences in Auschwitz, distinguished these two groups as the drowned and the saved.

Douglass recounts the harshness of the slave life, both the physical hardship of work in the fields (which he himself largely escaped, as it happened) and the hunger and cold (which he did not). Beatings and whippings were a common feature of this life, whether for any of a host of minor infractions, or purely on a whim. One slave owner in Baltimore would strike out at her slaves as a matter of course, whenever they passed by. While other slave holders disapproved of this excessive behaviour, none, Douglass noted, would have questioned her right to beat her slaves.

The violence of slave life is amply represented in popular culture, from 12 Years a Slave to the cartoonish Django, but Douglass also emphasizes the way that slaves were denied a family life, not only denied the option of legal marriage, but regularly split up and sold to different parts of the country. Douglass was raised by his grandmother and scarcely met his own mother. He was surprised to find, on moving to the main plantation as a boy that he had brothers and sisters, although, unsurprisingly, they were never to become close. Sociologist, Orlando Patterson, described this as a sort of ‘social death’ experienced by slaves, whose relationships could be ended at any moment by their masters and who were compelled to live with this possibility hanging over their heads.

The essence of slavery, Douglass points out, does not lie in the harsh treatment to which slaves were regularly subjected, but rather in the status of being a slave. Douglass himself was fortunate enough to be sent away to the city rather than to the fields. There he managed to learn to read and write and life was comparatively comfortable. However, a ‘slaveholder, kind or cruel, is a slaveholder still‘ – it makes no difference to one’s slave status. To be dominated, i.e. in the power of a master, a dominus, is, in the words of political philosopher, Philip Pettit, to be exposed to the possibility of uncontrolled interference in one’s life. It is this persistent vulnerability to others who may mistreat you with impunity, that is central to domination rather than individual incidents of brutality. A kind master is preferable to a cruel one, but both have the same power over the slave and nothing compels them, if they happen to be kind, to remain so.

Living with this vulnerability can take a heavy toll on those concerned. This is not simply a matter of damaging one’s well-being, but of potentially warping one’s relation to oneself, diminishing one’s sense of self-worth and self-respect. Douglass reflects that slaves commonly adopted a servile attitude in the hope of deflecting the attention of the master. In time, however, servility can become a role from which one cannot escape. The ancient Stoic philosopher, Epictetus, himself a former slave, recommended reflecting on the transience of this life, not simply as an aid to enduring its hardships, but to enduring them with one’s dignity intact. Maintaining one’s dignity might sound like a rather rarified concern, but for Douglass, as for so many others, it was a matter of life and death. In the most dramatic passage of Douglass’ narrative, he recounts how he refused to accept a beating from an especially brutal overseer, even though in doing so he risked his life. Victorious in the struggle, Douglass says that, ‘I had reached the point at which I was not afraid to die. This spirit made me a freeman in fact, while I remained a slave in form.’

Douglass always insisted, with good reason, that chattel slavery, in which one is legally nothing more than a piece of property, is the most intense form of domination. The end of the slave system which sustained these relationships, however, did not simply eliminate race-based domination. The end of slavery proper did not, as Douglass found, securely establish the equal status of black people. Securing people against domination is a complex matter, requiring the restructuring of laws, institutions, and social attitudes. Alongside more subtle and insidious forms of oppression and inequality, we continue to see the persistence of unusually intense forms of domination, as George Floyd’s recent death has shown yet again. The bare minimum that a decent society can provide is security against this sort of treatment and yet it appears that this still cannot be guaranteed, 155 years after slavery itself was abolished in the US.