Francine Rossone de Paula

Lecturer in International Relations

31/05/2020

In Belfast, groups of up to six people who do not share a household can meet up outdoors after the relaxation of lockdown last 25 May. There is now more movement in parks and public spaces. Despite the reputation of the city for its bad weather, the past weeks have been incredibly warm and sunny, and it feels alive as people gather under the sun and bright green trees.

Belfast looks beautiful. The sight of so many people at the Botanic Gardens and the sound of excited teenagers meeting their friends after months in isolation bring us a sense of normality so many of us have been craving. Are we slowly but finally returning to life as it used to be?

Imagining the possibility of returning to normal soon is inspiring, but it can also be extremely disturbing when we lose sight of what “normal” entails. I confess that instead of hope, I have responded to the repetition of “this shall pass” everywhere with some dose of anger and frustration since the beginning of this health crisis. While we all want things to get better, “crisis”, or a sense of “state of emergency”, is unfortunately a normalized condition of the everyday of minority groups in various societies. For these groups, “normal” means the continuation of a suffocating, threatening, and oppressive reality. It does not even make sense to talk about a return to normal when the current abnormality only exacerbated vulnerabilities without necessarily representing a rupture with how things used to be before COVID-19.

Normal in mathematics represents a symmetric distribution where cases cluster around the center, forming a bell-shaped curve. Normal, from the Latin word normalis, also means, more specifically, according to the rule or pattern. Considering these definitions, we could start by challenging claims that our pre-Covid-19 world was “normal”.

A report from the Credit Suisse Global Wealth from 2019 found that the world’s richest 1 percent own 44 percent of the world’s wealth. Does that sound normal? The 2019 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index shows that 1.3 billion people worldwide are ‘multidimensionally poor’, and contrary to what one may assume about where these people are located, this study reveals that 2/3 of multidimensionally poor people live in middle-income countries.

Worldwide, research projects are now investigating closely the relationship between COVID-19 and poverty. The World Bank has published last April a policy brief about Poverty and Distributional Impacts of COVID-19. The recommendation is that governments monitor and respond to the situation by implementing programs tailored to each context. The goal is to “mitigate” the impact. But what happens after the impact is mitigated? How is success or effectiveness going to be measured? Are we planning to go back to “normal” neoliberal agendas that reject any form of governmental programs aimed towards welfare and/or distribution of income?

The impact of the pandemic on people is not only disproportionally distributed according to their postcode, but also according to color and ethnicity. A video circulated in social media recently shows a doctor in the Mathira area of Uttar Pradesh, in India, affirming that they would only treat Hindus, not the Muslims. In Brazil, the population in favelas continues to be “found” by bullets and police operations have become even more aggressive during the pandemic. João Pedro Mattos, a 14-old boy from the favela complex of Salgueiro in Rio de Janeiro, was playing with his cousin in his living room when he was hit by a bullet during a police operation. An investigation of this case reveals that there were 72 bullet marks in the walls of this family’s house, what dismisses any affirmation that this was a stray bullet.

According to a report by the Research Network Observatories of Security and the Centre of Studies in Security and Citizenship (CESeC), there was an increase in 56% in the lethality of police operations in 2019 (from June to October) in Rio de Janeiro alone. The latest data released by the Institute of Public Security (ISP), an organ associated with the State of Rio de Janeiro, shows that in April of 2020, as lockdown restrictions were more strictly imposed, there was an increase of 43% of deaths resulting not from COVID-19, but from police operations, in relation to the same period last year. In a single month, 177 people were killed in interventions by the State, affecting black people disproportionally.

It would be easy to blame violence against citizens on the fact that Brazil is a “developing” or a “third world” country. However, this is further from the truth. The Washington Post’s database contains records of every fatal shooting in the United States by a police officer since 2015, and their data shows a total of 1,004 people killed by police in 2019, of which 23% were black. The number is even more significant when we consider that the Black or African American represents about 13,4% of the American population.

George Floyd was one amongst many individuals victimized by a public security system designed to fail those who fall out of the standard, culturally, politically, or economically. In other words, a system who has always failed by design those positioned outside of what is historically valued as “normal”. In that sense, the normal is suffocating and invisibilising. Floyd’s last words are very emblematic: “I can’t breathe”.

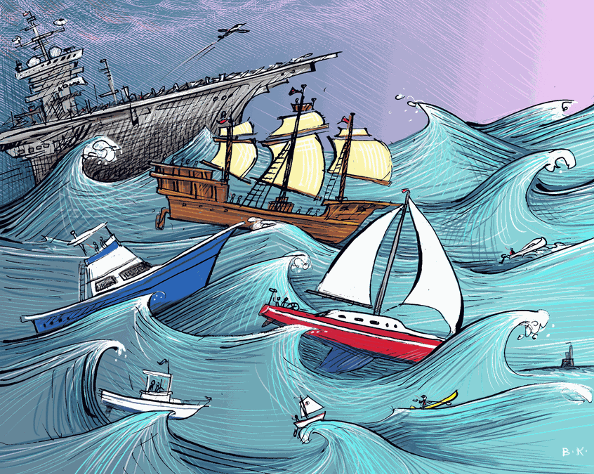

Minorities everywhere are constantly suffocated by the “sovereign State”, the rules, the standards, the expectations, and so on. Regardless of lockdown restrictions being imposed or lifted, their rights to come and go within their own societies or host countries have never been reliably honored. Their rights to go outside in groups and gather in public spaces are frequently seen with suspicious and severely repressed in that same world we called “normal”. So many people every year are drowned in the sea trying to flee persecution and/or misery, and terrified by the impossibility of ever meeting expectations of being “normal” or living a “normal” life.

The viral phrase says, “We are all in the same storm, but not in the same boat.” As the storm resigns, there will be a lot of people still drowning and struggling with what “we” consider from this more privileged side an “ordinary wave”. Racism and inequality are as destructive and have a much longer history than coronavirus. As we hope for a definitive solution for coronavirus (hopefully a vaccine soon), the solution for that historical and long-lasting pandemic is a much more complicated issue. Those of us who have been lucky enough to be, to some extent, immune to the harsher effects of this other pandemic, should invest in the transformation of that condition and be part of the solution. First, one should at least wake up to the fact that it may be cruel to wish for “normality” as we know it.

This debate is much more complex that it could be expressed in a blog post, but to the question “Are we returning to normal?”, my answer is I hope not!