What does a rainbow mean to you?

What does a rainbow mean to you?

I went to a Black Lives Matter protest and saw women in their late sixties protesting against police brutality, racial profiling, systematic abuse and mistreatment and I wondered how tiring and painful it must be for them as mothers and grandmothers to have to beg and protest just to be treated equality every day of their lives. I saw babies there no older than 1 or 2 and I wondered if they would have to spend their lives doing the same, filled with rage at how this was still happening, and then I went home.

I left with friends, planning on when we could meet up again, complaining about when we would ever return to “normality” after this pandemic, my anger shifting to the loss of holidays, nights out, and losing hours at work.

I went to the shop and bought snacks, holding my sign and then boarded a bus all while passing by police, vaguely aware of their presence, undisturbed by them.

At home, my mind already drifted onto online shopping, scrolling through fast fashion websites like Urban Outfitters and Pretty Little Thing with extreme right wing racist and trans-phobic CEOs, justifying abandoning my morals by clothing that was just too cute to not buy.

I listened to my friends’ excuses for not being involved, for not signing petitions, attending protests or speaking out, “I’m not really political” or “something came up” and I also listened to those who didn’t give any, brushing it off.

I listened to family members ‘slightly’ racist jokes, ignoring but not confronting them or my own innate ignorance and prejudice opinions.

I remembered how, as a child growing up in New York City, that if I was lost, I was instructed to go to the police, learning to see comfort in their presence at late nights alone and to cheer and praise my heroes for their work, angry at the few racist ‘bad apples’.

I listened to the news of the heightened charges against Derek Chauvin, now facing second degree murder, along with his colleagues now facing charges for accessory to murder, happy that justice was achieved, but then my phone lit up with the details of the murder of David McAtee, the African American man known for handing out free meals to police officers, shot by officers during these protests who had turned off their body cams, claiming to be only “returning fire”, whilst trying to protect his injured niece and other peaceful protesters rushing to take cover under the flurry of pepper balls and rubber bullets, his body lying in the street for 12 hours. Then I remembered all the names that hadn’t received justice, whose murders still walked free: Elijah McClain, Breonna Taylor, Toyin Salau, Eric Gardener, and all the names I didn’t remember and I wondered if we really achieved anything at all, if we were destined to continue to fight for the same things, five minutes, five days, years, centuries on, and why this was the case.

And then I realized how little I had actually done.

I realized how easy it was for me to shed my sign, to walk home, to walk to the store, to complain about the ‘new normal,’ an ‘invisible’ privilege people of colour never have. Their lives have never felt my ‘normal’ of being able to ignore the police presence, or breathe a sigh of relief for police who have never been their heroes but enemies, being no such thing as a ‘bad apple’ if each cop represents a systemically racist system, only being worse apples among a horrific bunch, of mindlessly consuming and supporting racist and trans-phobic leaders who for them don’t just have ‘different views’ but a view that seems them as sub-humans, views which could kill. I realized they couldn’t indulge in the luxury of not being political, because their lives were at stake if they didn’t, because they had to keep fighting to make sure that they retained any equality whilst I was handed mine.

I realized that my half-assed allyship of attending rallies against racism or posting for a few days isn’t enough and that the reason this keeps happening is because for me, this is a trending event one so easy for me to forget about and ignore if it becomes too much. But for people of colour, these events are an unforgettable reminder, every new victim serving as a harrowing example of who they could be, what they face.

I will never be in the same position as these victims, as my friends. I understand that I will never understand their pain or fear. My white skin is a shield from the brutality they face and that’s exactly why I must do better and use my enormous privilege to make change. To stand in solidarity with my peers of colour and amplify their voices and call out myself and my white peers’ ignorance. To risk cutting off friends, family and opportunities to stand against racism. To even risk not shopping at ‘trendy stores’ and to be consistently pushing for change for systematic racism inherent in every corner of our societies that have granted me my privilege, not just for a few minutes or hours but forever. Without doing so, these issues are destined to permanency.

Why study an MA in Irish Studies at Queen’s? Hear more about this unique interdisciplinary programme from academics and students.

What’s it like to study an MA in Public History at Queen’s? The course director, Dr Leonie Hannan, recently held a webinar on this unique programme. You can watch it below to find out more.

What’s it like to study an MA in Conflict Transformation and Social Justice at Queen’s? The course director, Dr Fiona Murphy, recently held a webinar on this unique programme. You can watch it below to find out more.

In this short video, political scientists at Queen’s University Belfast – Dr Muiris MacCarthaigh, Dr Elodie Fabre, Dr Andrew Thomson, and Dr Stefan Andreasson – share their perspectives on COVID-19’s impact on the study of politics.

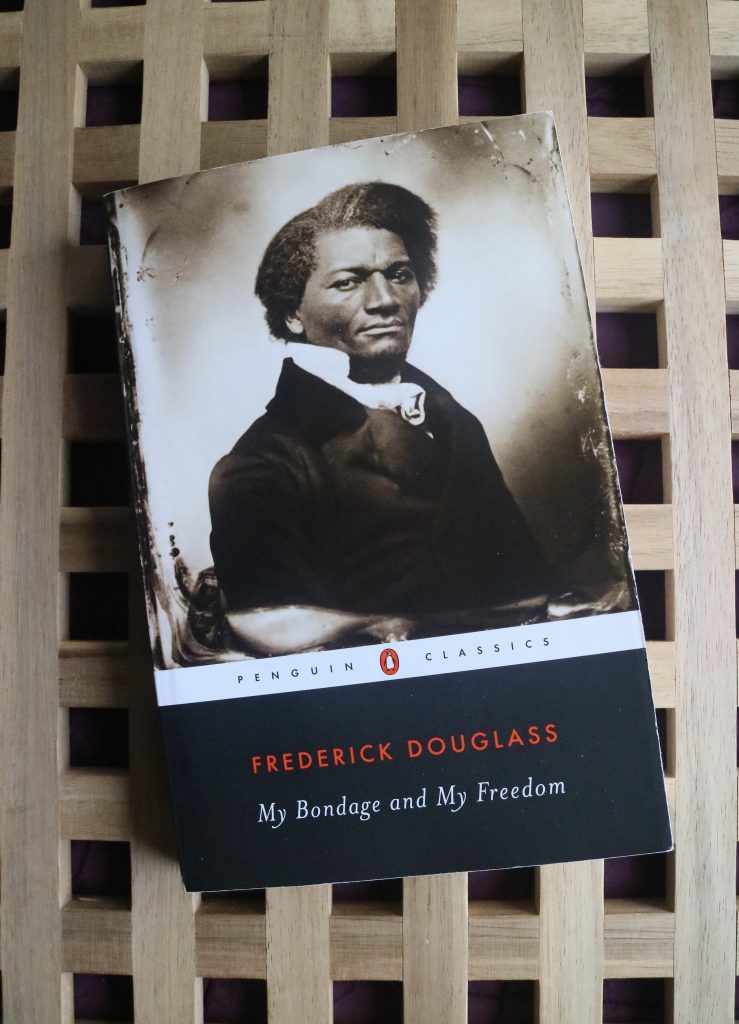

‘The first work of slavery is to mar and deface those characteristics of its victims which distinguish men from things, and persons from property’. These are the words of Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery in Maryland to become a leading campaigner for the abolition of slavery and for the rights of Black people. Besides his work as a public speaker, journalist and newspaper editor, Douglass also wrote a biography – publishing three versions of it in his lifetime – reflecting on his life in slavery and his subsequent emancipation, of which My Bondage and My Freedom was the second version.

I became interested in the experiences of figures like Douglass and his contemporary, Booker T. Washington, former slave and noted educationalist, when researching questions of recognition and respect. I was especially interested is the way in which people subject to the most extremely harsh and degrading treatment could nonetheless retain their self-respect in such conditions. While others were unable to resist the relentless humiliations heaped on them by their captors, some people nevertheless managed to hold onto their sense that they were entitled to be treated as equals. Primo Levi, writing about his own experiences in Auschwitz, distinguished these two groups as the drowned and the saved.

Douglass recounts the harshness of the slave life, both the physical hardship of work in the fields (which he himself largely escaped, as it happened) and the hunger and cold (which he did not). Beatings and whippings were a common feature of this life, whether for any of a host of minor infractions, or purely on a whim. One slave owner in Baltimore would strike out at her slaves as a matter of course, whenever they passed by. While other slave holders disapproved of this excessive behaviour, none, Douglass noted, would have questioned her right to beat her slaves.

The violence of slave life is amply represented in popular culture, from 12 Years a Slave to the cartoonish Django, but Douglass also emphasizes the way that slaves were denied a family life, not only denied the option of legal marriage, but regularly split up and sold to different parts of the country. Douglass was raised by his grandmother and scarcely met his own mother. He was surprised to find, on moving to the main plantation as a boy that he had brothers and sisters, although, unsurprisingly, they were never to become close. Sociologist, Orlando Patterson, described this as a sort of ‘social death’ experienced by slaves, whose relationships could be ended at any moment by their masters and who were compelled to live with this possibility hanging over their heads.

The essence of slavery, Douglass points out, does not lie in the harsh treatment to which slaves were regularly subjected, but rather in the status of being a slave. Douglass himself was fortunate enough to be sent away to the city rather than to the fields. There he managed to learn to read and write and life was comparatively comfortable. However, a ‘slaveholder, kind or cruel, is a slaveholder still‘ – it makes no difference to one’s slave status. To be dominated, i.e. in the power of a master, a dominus, is, in the words of political philosopher, Philip Pettit, to be exposed to the possibility of uncontrolled interference in one’s life. It is this persistent vulnerability to others who may mistreat you with impunity, that is central to domination rather than individual incidents of brutality. A kind master is preferable to a cruel one, but both have the same power over the slave and nothing compels them, if they happen to be kind, to remain so.

Living with this vulnerability can take a heavy toll on those concerned. This is not simply a matter of damaging one’s well-being, but of potentially warping one’s relation to oneself, diminishing one’s sense of self-worth and self-respect. Douglass reflects that slaves commonly adopted a servile attitude in the hope of deflecting the attention of the master. In time, however, servility can become a role from which one cannot escape. The ancient Stoic philosopher, Epictetus, himself a former slave, recommended reflecting on the transience of this life, not simply as an aid to enduring its hardships, but to enduring them with one’s dignity intact. Maintaining one’s dignity might sound like a rather rarified concern, but for Douglass, as for so many others, it was a matter of life and death. In the most dramatic passage of Douglass’ narrative, he recounts how he refused to accept a beating from an especially brutal overseer, even though in doing so he risked his life. Victorious in the struggle, Douglass says that, ‘I had reached the point at which I was not afraid to die. This spirit made me a freeman in fact, while I remained a slave in form.’

Douglass always insisted, with good reason, that chattel slavery, in which one is legally nothing more than a piece of property, is the most intense form of domination. The end of the slave system which sustained these relationships, however, did not simply eliminate race-based domination. The end of slavery proper did not, as Douglass found, securely establish the equal status of black people. Securing people against domination is a complex matter, requiring the restructuring of laws, institutions, and social attitudes. Alongside more subtle and insidious forms of oppression and inequality, we continue to see the persistence of unusually intense forms of domination, as George Floyd’s recent death has shown yet again. The bare minimum that a decent society can provide is security against this sort of treatment and yet it appears that this still cannot be guaranteed, 155 years after slavery itself was abolished in the US.

Over the last few months, for obvious reasons, I’ve been thinking about the 1918 flu pandemic. Although I’ve written a book about the 1920s and I teach the history of inter-war Europe, the 1918 flu pandemic is not an event that I had thought or read too much about, up to now. I picked up Laura Spinney’s excellent book, Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and how it changed the World to try and find out more about what she calls the ‘elephant in the room’ of the history of the early twentieth century.

My first book was on the Italian intellectual, journalist and editor Piero Gobetti, one of the earliest and most vocal opponents to Mussolini. He died in 1926 and lived his entire public life in the early 1920s, beginning his career as an editor in November 1918 when he began to publish his first political magazine Energie Nove. It’s been a number of years since I left the 1920s behind and I’ve been working since then on the 1950s and 1960s, but in light of the current pandemic and with the benefit of some distance from the 1920s, I’ve been thinking again about why I never came across any mention of the 1918 pandemic (or just didn’t notice the signs of it?) during my time researching Gobetti and the 1920s.

Gobetti was beginning his career as an editor, intellectual and journalist at a very turbulent time. The war was just over in November 1918, when Gobetti brought out the first issue of his political magazine. Italy was on the side of the victors although the Italian military performance had been pretty disastrous. In the northern city of Turin where Gobetti lived, there was also a lot of social unrest. Turin’s factories had kept the war effort going through the production of armaments although the urban working classes were suffering severe food shortages by the end of the war. Bread riots coupled with the return of resentful, unemployed veterans made for an autumn and winter of social tension, and the widespread feeling that something had to change. Gobetti did not fight in the war himself as he was only barely eighteen when the armistice was signed. He nevertheless had the feeling, like so many his age and a little older, that the impact of the war was so huge that some kind of renewal, or change for the better, had to come out of it.

Although there are no mentions of the Spanish ‘flu in any of Gobetti’s magazines, his published writings nor his correspondence, we know that while he and those of his generation were reeling at the impact of the war and clamouring for some kind of change, there was another killer in their midst. The peak of the pandemic was in autumn 1918, with the particularly lethal second wave raging through the world between October and December of that year. The somewhat milder third wave was in January 1919 while the virus had largely petered out by that spring. It is now estimated that between 50 and 100 million died in the 1918 pandemic, and in Italy the death toll is thought to be somewhere around 300,000. This is close to the figures we have for those Italians who died in combat during the Great War, but the post-war years are filled with endless discussion of the war and barely any mention of the ‘flu pandemic. Why was this?

The reasons may lie partly in the kind of world that people inhabited in 1918. It was one where illness and disease were commonplace enough. People were used to epidemics of cholera, typhoid and flu, while TB and in rural, marshy areas of Italy, malaria, were endemic. The discovery of antibiotics was still several decades away and for many of these illness, there was nothing much that conventional medicine had to offer. Mortality from diseases such as these, especially in childhood, was much more common. For those who survived, long periods of illness and convalescence were to be expected, while many were also left with the long-term effects of their disease. All of this was part of the harsh, everyday brutality of life for so many; Gobetti himself suffered from ill health and died in 1926 from a combination of ill health and injury, after a series of fascist beatings. Antonio Gramsci, the first leader of the Italian Communist Party and a contemporary of Gobetti’s in Turin, also suffered ill health and a long term disability, possibly due to TB. Although the 1918 pandemic was unique in its ferocity, it may have taken some time for this to be understood at a time when death from disease was more sadly ordinary than it is in the twenty-first century.

Death from flu, as Spinney reminds us, was also a private, family affair, with most dying in the home rather than in hospitals. Although it was happening all around them, since each death was individual, it may be that the full collective impact was only appreciated afterwards. The war in contrast was entirely new and different; the use of mechanised warfare, and the sheer scale of the conflict, made it clear to everyone at the time that this was an event like no other. It came with entirely new whole sights and sounds, from mass mobilization and trenches to the sound of rapid machine gun fire. Flu was a more quiet and apparently ordinary killer. I am beginning to wonder though the ‘flu pandemic did play some part, even indirectly, in Gobetti’s thinking. In late 1918 he wrote to another journalist that he wanted his magazine to be a ‘sign of renewal’ in ‘this dead Turin’. Could the lethal virus that was flaring through his city really have no part in this vision of tiredness, disillusion and death? Elizabeth Outka, in her work on the impact of the 1918 ‘flu on literature, found that the imprint of the pandemic ran right through the literature of the 1920s, once you knew where and how to look.

In the final chapter on the memory of the 1918 pandemic, Laura Spinney suggests that while the impact of war is felt and recognised immediately afterwards, it takes much longer for the full shape of a pandemic to emerge from the messy immediacy of history and for its true scale and impact to be appreciated. While the enormity of the Black Death is now well known, it may not have been fully understood at the time or immediately afterwards. However she argues that while the intensity of war fades in collective memory, a pandemic may come more sharply into view with time. Will we in time remember the 1918 pandemic much more vividly than we do now, while the First World War fades somewhat into just one of an endless list of human conflicts? It’s an intriguing prospect for historians of the European twentieth century. One might wonder too how the current Coronavirus pandemic will be remembered by future historians. I think, given the virtually worldwide experience of lockdown, coupled with the fact that we are not quite as used to living with disease as were the men and women of 1918, that we are already appreciating this pandemic as an event of global significance. At the same time it is very likely that the ways in which we apprehend and understand it, will change over time.

It was June 8th, 2020, 2.30 in the afternoon, I got a call from my mother who lives in Lucknow around 130 miles from my place. She was a bit worried and directly asked me a question- is it safe for Nitin (my brother) and his family to stay back in Gurugram (Gurgaon that is around 20 miles from Delhi) as Delhi recorded a seismic activity of 2.1 on Richter scale? It was the eleventh shock that Delhi recorded. Some were felt by the residents of the adjoining areas and others were reported in the media. She told me that she has read that an earthquake of a bigger magnitude is inevitable and can happen anytime soon. Delhi falls in a zone that is seismically very active and a massive earthquake is long overdue in the Himalayan region. She wanted his family to come over to Lucknow for some times. But how will they travel? Is it safe for them to travel in the pandemic? They can travel by their own car? For how long they can stay? These were her concerns. She also knew that there is no forecast for earthquakes and there were also counter narratives in the media that say that such tectonic activities are common but still they all warn that an earthquake is bound to come. How to make sense of all this? It was December 20th, 2019 (Corona pandemic still a couple of months away to jolt India) that an earthquake with its epicenter in Hindu Kush region of Afghanistan shook Delhi and adjoining areas, my parents were with my brother at that time and it was quite a panic that was created as they live on the 10th floor of a high-rise building.

Our conversation then shifted to the dangers of living in a high-rise building and the construction norms that we all thought were not followed by the builders in general. In case of a disaster the building may come down like a pack of cards. We realized that we generated such risks for ourselves. I was reminded of Ulrich Beck who talked about the risk society and how we are manufacturing risk to our own peril. Soon my father cracked some old common family joke on which my mother took great objection as she said how you guys could laugh away such a serious issue. But actually we all knew that we know nothing how to resolve the issue. I could realize however, that our experience is similar to what Immanuel Kant writes in his ‘Analytic of the sublime’, where he suggests that sublime is a pleasure produced by the mind as soon as it reaches its own limits. The humiliation of the mind through the thoughts of destruction and loss is overcome soon by the mind itself that restores its power by reckoning its own superiority to the nature. How many times it happens that when we cough in these times we look at each other in the family and give a smile-nothing to worry, as we cannot do much about anything that is happening around us.

Nightmares are coming true. It’s like living a disaster movie with all its dimensions (Ds). Pandemic was not enough. A super cyclone Amphane wrecked havoc in India, Bangladesh and Srilanka in May, 2020. The Chief Minister of Bengal where the cyclone made a landfall described the effects of the cyclone as worse than the pandemic.

Disasters are not defined only in terms of scientific and administrative norms. People tend to have their own explanations based on absorbing principles of Karma or appealing principles based on folk models. Consequences of one’s Karma are inevitable and owing to large scale destruction to the environment we cannot protect ourselves from the wrath of the Mother Nature. Alternatively, it is also believed that appeasement of the deity ensures safety and any shortcoming in this may lead to destruction. With such theories doing the round, people making sense of the crisis through themand science not coming to the rescue of people, thought of another disaster striking in the midst of the pandemic does not seem to be very far away or unbelievable.

On June 9th, I woke-up reading a headline in a Hindi newspaper that read- ‘The city (Prayagraj, where I stay) is coming back to its flow (translated from Hindi).’ With Malls, restaurants, places of worship and other public places opening-up there is a sense of getting back to the normal. On June 10th, in an English daily I saw a photograph of a hoarding stuck high and bold on a street of Lucknow that read- ‘Lucknow please smile as the life has started again (translated from Hindi).’ This photograph of the hoarding was placed under the headline-“Ambedkarnagar hospital chief dies: record jump in single-day fatalities.” People were still fighting out the infection within the projections of normalcy through such advertisements. The newspaper is sensitive enough to have brought this to our conscious thinking.

How can this paradox be explained? Behind the statistical data, we are actually missing out the pain and sufferings of the people. Their hardships are unfathomable through statistical models.We can only imagine a four year old child kept in isolation for 14 days and asking her mother, “can I come to your lap now mom?” Only very selected stories of mental agony and suffering are seeing the light of the day and are getting reported in the media.News reports of people not getting proper care, not being admitted to any hospital in some places, or not being tested even after reporting symptoms are common now. People are dying without their loved ones getting the opportunity to see their faces for the one last time. Much more needs to be known, not only about people’s suffering but about the meaning they are giving to their sufferings. How do people make their sufferings sufferable? A narrative of ‘normalcy’ might be on the agenda of the state, however the ‘lived reality’ lies between the pandemic and the data dashboard.

On June 10, Trócaire hosted a webinar in which we discussed how lockdown restrictions are impacting the work of brave human rights activists who were already facing grave danger in defending indigenous communities. As we recover from the pandemic, it is more important than ever, that we call for regulation to hold corporations to account for human rights violations. The discussion included a political analysis of introducing human rights and environmental due diligence legislation in the UK and Ireland.

You can watch back here: