Cillian McBride

Senior Lecturer in Political Theory

21/05/2020

Outside of a dog, a book is man’s best friend,’ observed Groucho Marx, before adding that, ‘inside of a dog, it’s too dark to read…’ In these dark times, we can at least read and so I thought I might suggest something to add to everyone’s lockdown reading list. Perhaps something utopian/dystopian from the world of sci fi would be best but my pick is just something that struck a chord with me. I’ll try to shoehorn in a Covid-19 link by the end, if I can. Don’t worry about missing it: it probably won’t be subtle.

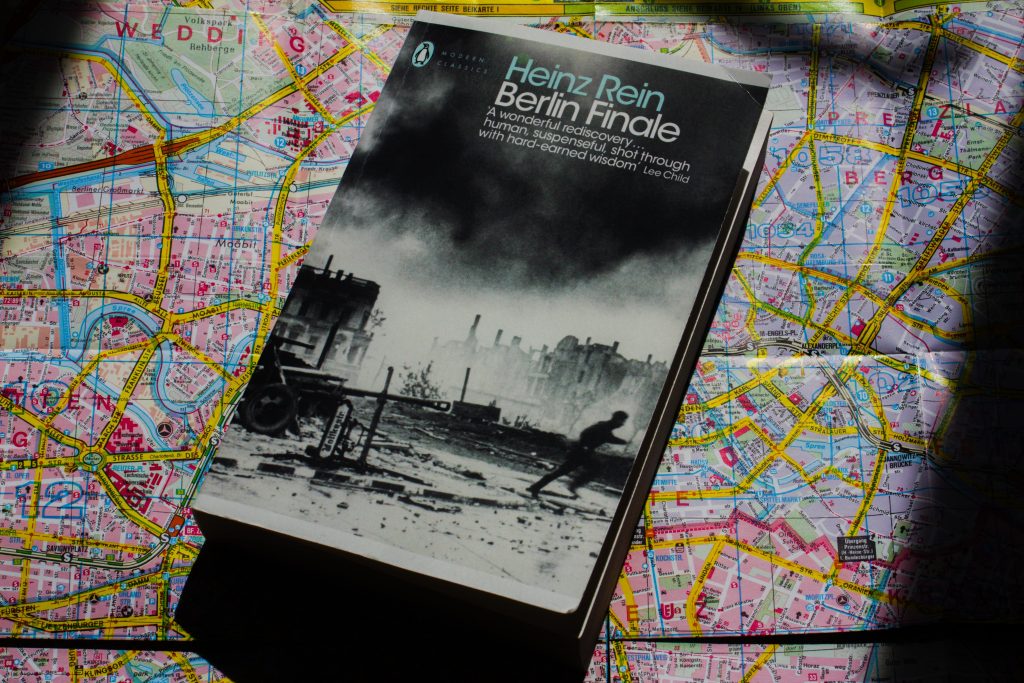

The book I have in mind is one I read earlier this year in that happy pre-lockdown period when it was still bliss to be alive (this may be a slight exaggeration. Belfast in January is not Paris in spring, or so I’ve been told). It’s Berlin Finale by Heinz Rein. I hadn’t heard of it before: it was just something that caught my eye one day in a bookshop. The virtue of browsing in actual bookshops is the limited stock, forcing you to be flexible if you want to come out with any sort of a book to read. Second-hand bookshops are especially good in this regard as they may contain just one solitary book that you might actually consider reading and it usually takes some hunting to find it. One Swansea bookshop I knew simply dispensed with any attempt at organisation whatsoever with the result that no shelf could be safely left unexamined. I’m not sure I still have the stamina for that sort of thing.

Having spent the summer of 1989 in Berlin (missing the fall of the Wall, naturally, but at least getting to peek behind the Iron Curtain while it was still hanging), I have a soft spot for all things Berlin. Rein’s book deals with the closing days of the war and the efforts of a collection of surviving leftists to stay alive until the Russians arrive, trying to stay out of the clutches of the remnants of the Nazi regime without also getting themselves killed by their Russian liberators in the confusion. The book was written shortly after the war and Rein punctuates it with passages of Nazi propaganda hailing non-existent German victories as the Russians grow ever closer.

What really drives the book is its outrage at the complicity of the ordinary population with the regime, the day to day compliance of most citizens, interspersed with enthusiastic cruelty on the part of the genuine fanatics. Rein’s heroes, the few who held out and quietly resisted the regime, worry that a whole generation may have been poisoned by growing up in Hitler’s shadow.

The question of complicity appealed to me because I’m interested in the ways our social relationships pull us this way and that. This sets the scene for social and political struggles over whose voices are recognised as authoritative, which expectations we have to navigate around and which ones we end up internalising. One familiar response to these pressures is to strike the pose of the heroic individualist who casts off all social entanglements in the name of personal freedom. This strikes me as a poor response, not only because it is ultimately an impossible goal, but also because it also looks a lot like a cop-out. We are inextricably caught up in social life, weighing the demands of others and making demands on others in turn, vulnerable and potentially dominating in turn. If we refuse to acknowledge this, we aren’t even going to begin to think about our responsibility for the various roles we play in life.

A different sort of mistake is that of the angry moralist who wants to judge everyone equally guilty for collective outcomes because we were all involved in some way or another. Famously, philosopher Karl Jaspers claimed that all Germans bore ‘metaphysical guilt’ for the holocaust. This seems excessive: surely we bear different degrees of responsibility depending on the different roles we play? Attributing responsibility is a tricky business. The reckless populist leader who tries to undermine the public health policies during a pandemic bears more responsibility for the resulting failures than his media-befuddled supporters (to pluck an example out of thin air, and, yes, this is the Covid-19 shoehorn bit. You were warned…) but they must bear some share of responsibility for putting him there in the first place.

One effect of the current crisis has been to bring to the fore the fact that our lives are deeply interdependent. Our daily lives are sustained by a vast complex scheme of social cooperation, stretching far beyond our borders, which goes largely unnoticed until parts of it stop functioning. We are responsible for our own contributions to this scheme, of course and when these are valuable we can take pride in them. But perhaps we are also complicit to some degree in sustaining of the more problematic patterns of interaction, those that damage the lives of others, whether through social and economic inequalities or environmental degradation. Being responsible, however, is not just a matter of looking back at the things we should have done differently, acknowledging the times when we should have resisted rather than complied, like Rein’s underground heroes. It is also a matter of looking forward, to the ways we can reshape our social relations.

The Greek historian, Polybius, believed that history moved in a circle. Human institutions were impermanent and when they were working well we could only hope to stave off decline for as long as possible before corruption set in. That was the bad news. The good news was that it was always possible, even when things looked most hopeless, that they might be set on the path to improvement. Whether we have grounds for cautious optimism about our future depends entirely on what we do next.