Ann-Marie Foster

Lecturer in Public History

21/05/2020

Watch Dr Foster’s recent talk and Q&A about public history in Northern Ireland for the International Federation for Public History.

Watch Dr Foster’s recent talk and Q&A about public history in Northern Ireland for the International Federation for Public History.

In Northern Ireland the Covid-19 lockdown started in the middle of March 2020 and by the 23rd we were officially social distancing. The fundamental reason for this strategy was to protect the National Health Service, the ‘front line’ for saving lives. At 8.00pm on 26th March people across the UK, most stuck in their homes, stepped out of their doors and leaned out of windows to acknowledge the NHS workers by clapping. This has been repeated every Thursday during the lockdown gaining widespread publicity. In addition, people have been displaying rainbows from windows also in support of the NHS.

For those of us studying anthropology, this immediate representation of our world through rituals, symbols and commemorations is not a surprise. People need to find ways of creating a sense of community, a sense of common activity, and doing so when restricted from the public sphere is an act of resistance as well as an affirmation of cohesion. And this has political ramifications.

We should not assume the meaning that participants are giving to these rituals. People have different reasons for participation. What I think can be suggested is the power of these events in terms of promoting cohesion in a neighbourhood and in support for the health service and the enhanced status given to its workers. The power of this apparent national consensus will play out in the politics that follows the lock down. The symbol of the rainbow has taken on new political meaning and this will be important.

The country was asked to observe a minute’s silence at 11.00am on 28th April for those key workers that have died. This was intended to coincide with International Workers’ Memorial Day on which people killed or injured at work are annually remembered. This commemoration was founded by trade unions in the US whilst in Canada, in 1984, a National Day of Mourning for workers was instituted. Since 2001 the United Nations has recognised it as The World Day for Safety and Health at Work. It is worth noting that whilst the Trade Union Congress cast this act of commemoration within this longer standing event this was lost in media coverage. I am willing to bet that British Prime minister, Boris Johnson, had not recognised this day in the past. But will he in the future?

The use of ‘11.00am’ and the minutes silence is also significant. In UK terms, it mimics the better know and better observed events on Remembrance or Armistice Day when a minute’s silence is also observed at 11.00am to remember those who lost their lives in the service of the military. We are of course well used to the way in which the monarchy and political elite line-up to be at the forefront of this event. But then this day is cast as of national remembrance enhanced by the idea that the conflicts the military serve in, are in all our interest: ‘The Died For Us’. This of course is not uncontested.

We might also note with concern that society sometimes appears better at commemorating the sacrifice of those who died in war than looking after those that ‘returned’. This would suggest that those in power find the act of commemoration easier (and cheaper) than the act of investing in the victims and survivors.

It is noticeable that this fits a common political discourse using war as a metaphor in dealing with the pandemic. As Costanza Musu has already cogently argued this war time imagery of the front line, soldiers, sacrifice, and an ‘army of workers’ (The Sun Newspaper) is compelling but also dangerous. It places the struggle within highly nationalistic tones marginalising the global nature of the problem. Already leaders around the world have attempted to depict it as an ‘invasion’ introduced by foreigners. It also casts those in caring and healing professions alongside the military.

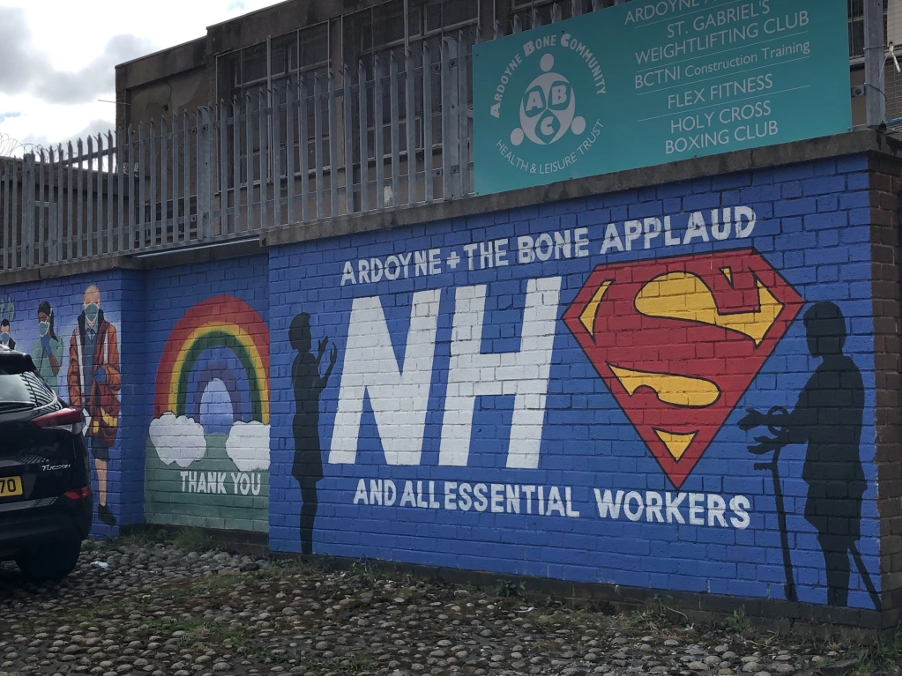

In Belfast there have been interesting local symbolic and ritual interpretations of the pandemic. There is evidence of common support for the institution of a public health service across the ethno-political boundaries that structure our society. As such, rainbows, which has become the symbol for supporting front-line workers, have appeared in windows across Belfast. The Thursday night doorstep clap has taken place regardless of the ethnic geography of the city. The NHS has been supported on murals on both sides of the ethno-political divide. Support for the NHS, popular with almost everyone, has been expressed in common public displays. Prior to March 2020 it was difficult to imagine a cause that could garner such universal backing.

Yet there are differences. The nationalistic approach to ‘combating’ the virus has been reflected in unionist areas of the city with the use of Union Jack flags, some with ‘Support the NHS’ and ‘Thank you to the NHS and all key workers’ written across them. Others have engaged with the militaristic analogy with banners saying ‘No Surrender to Covid-19’. The amazing exploits of 100 year old veteran, Tom Moore, who raised £30 million walking the length of his garden 100 times, was also depicted on a mural in Clonduff, East Belfast, along with his military medals and a rainbow (see above).

In Irish nationalist areas the narrative has been based on the rainbow and NHS staff as superheroes. Whilst I would not want to exaggerate these differences, as unionist areas have many representations that do not use the symbols of Britishness, there are nevertheless contrasts in commemorative symbols and narratives.

Why is this important? It is important because the financial and political implications of this, when the immediate crisis has past, will be enormous. The new symbolic status of the NHS and frontline workers will have a power that will be competed over by politicians. This will have massive ramifications for what gets publicly funded, and how. There is now competition with the military in the commemorative calendar. Consequently, who we depict as ‘defending’ the country will play out when government departments look at their budgets in years to come.

As a child, I lived in a small, rural village on the outskirts of Brno in the Czech Republic. My parents had built our house next to long stretches of gold wheat fields, in which my older brother and I spent most of our early childhood playing. Each spring, when the peach trees that surrounded our home would bloom pink, we’d stand on the edge of those fields and looked up to watch dark flocks of swallow birds dance in the blue sky, returning to Europe for the summer.

Because we were children, we welcomed them with joy and with fascination, but a part of us always felt sorry for them. Imagining tired wings which had travelled thousands of miles from their winter homes arriving in an unfamiliar, distant place. Imagining them lonely and displaced when they finally left the security of their familial flock to nest on their own. But we were children, and our little sorrows were quickly forgotten by a game of hide and seek or the sound of my mother’s voice calling us home.

I still search for them in the sky, all these years later. But green, rolling hills have replaced my yellow fields and heavy, grey clouds loom over the sunny memories of my childhood. I still wait for the swallows to return, no longer a child, but a migrant in a country that does not belong to me.

Northern Ireland has been in lockdown for almost nine weeks now, and despite social distancing restrictions slowly easing, while the number of coronavirus cases are on a daily decline world-wide, many people are feeling extremely lonely as a result of the pandemic.

Trapped in the relative safety of their homes to stop the spread of the virus, but unable to see their loved ones or gather with close friends. For me, the lockdown has brought back memories of my first few months here. The loneliness that came with moving to another country and the sense of aloneness I still feel from time to time as a settled ‘foreigner’, never quite fitting in. Even after fourteen years, it is a feeling that never really goes away.

For migrants like myself, this feeling of isolation is nothing new. We are no strangers to being alone. We have carried this grief with us for many years, and while we’ve been living with these feelings unknowingly or even secretly, this pandemic has opened up old wounds and an all too familiar sense of loneliness and loss. The loss of family and friends, the loss of being unable to be with those you love most. The loss of access to basic services and resources. The loss of your identity and even your sense of belonging.

So while the coronavirus pandemic has come as a shock to much of the world’s population, migrants have been faced with a reality that hits very close to home indeed. In the strange times of Covid-19, amongst an extreme feeling of aloneness that most of the population is experiencing, and with social distancing measures separating us from our loved ones, we have all become expats of an old world – a world that we may never get back. In less than three months, we have all become displaced within our own lives. In less than three months, we’ve had to redirect our paths and even our long-term futures. And in this way, we have all become migrants. Displaced refugees drifting to an unknown and an uncertain destination.

But there is something we can all learn from the migrant experience, something that may even help us during these challenging times. Because despite the pain of separation and loneliness, for migrants like myself, there is always hope. An undying faith in that eventually, we will overcome the barriers of distance and return to those we love. And it’s my hope that we all learn to live the migrant way. It’s my hope that we have the power to pick up our lives where they have been unexpectedly dropped on the ground, and that we all find the the strength to begin anew, even despite our losses.

So hold on, for just a little while longer. Because like swallow birds, we will eventually join our beloved flock. Soar to the skies at the turn of the seasons and finally begin to make our way back home.

Outside of a dog, a book is man’s best friend,’ observed Groucho Marx, before adding that, ‘inside of a dog, it’s too dark to read…’ In these dark times, we can at least read and so I thought I might suggest something to add to everyone’s lockdown reading list. Perhaps something utopian/dystopian from the world of sci fi would be best but my pick is just something that struck a chord with me. I’ll try to shoehorn in a Covid-19 link by the end, if I can. Don’t worry about missing it: it probably won’t be subtle.

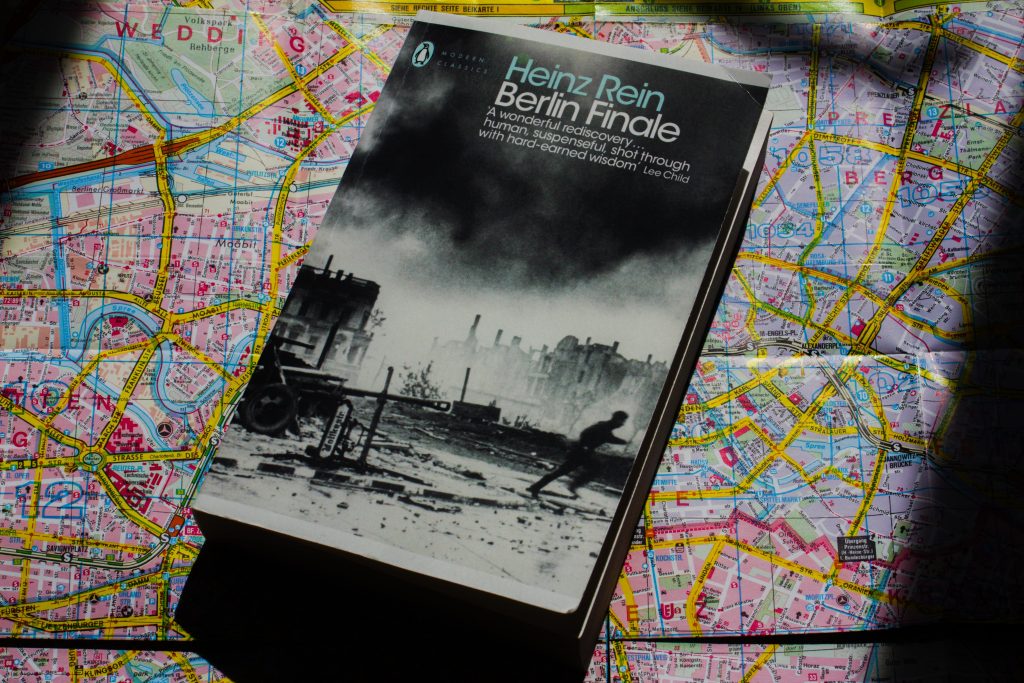

The book I have in mind is one I read earlier this year in that happy pre-lockdown period when it was still bliss to be alive (this may be a slight exaggeration. Belfast in January is not Paris in spring, or so I’ve been told). It’s Berlin Finale by Heinz Rein. I hadn’t heard of it before: it was just something that caught my eye one day in a bookshop. The virtue of browsing in actual bookshops is the limited stock, forcing you to be flexible if you want to come out with any sort of a book to read. Second-hand bookshops are especially good in this regard as they may contain just one solitary book that you might actually consider reading and it usually takes some hunting to find it. One Swansea bookshop I knew simply dispensed with any attempt at organisation whatsoever with the result that no shelf could be safely left unexamined. I’m not sure I still have the stamina for that sort of thing.

Having spent the summer of 1989 in Berlin (missing the fall of the Wall, naturally, but at least getting to peek behind the Iron Curtain while it was still hanging), I have a soft spot for all things Berlin. Rein’s book deals with the closing days of the war and the efforts of a collection of surviving leftists to stay alive until the Russians arrive, trying to stay out of the clutches of the remnants of the Nazi regime without also getting themselves killed by their Russian liberators in the confusion. The book was written shortly after the war and Rein punctuates it with passages of Nazi propaganda hailing non-existent German victories as the Russians grow ever closer.

What really drives the book is its outrage at the complicity of the ordinary population with the regime, the day to day compliance of most citizens, interspersed with enthusiastic cruelty on the part of the genuine fanatics. Rein’s heroes, the few who held out and quietly resisted the regime, worry that a whole generation may have been poisoned by growing up in Hitler’s shadow.

The question of complicity appealed to me because I’m interested in the ways our social relationships pull us this way and that. This sets the scene for social and political struggles over whose voices are recognised as authoritative, which expectations we have to navigate around and which ones we end up internalising. One familiar response to these pressures is to strike the pose of the heroic individualist who casts off all social entanglements in the name of personal freedom. This strikes me as a poor response, not only because it is ultimately an impossible goal, but also because it also looks a lot like a cop-out. We are inextricably caught up in social life, weighing the demands of others and making demands on others in turn, vulnerable and potentially dominating in turn. If we refuse to acknowledge this, we aren’t even going to begin to think about our responsibility for the various roles we play in life.

A different sort of mistake is that of the angry moralist who wants to judge everyone equally guilty for collective outcomes because we were all involved in some way or another. Famously, philosopher Karl Jaspers claimed that all Germans bore ‘metaphysical guilt’ for the holocaust. This seems excessive: surely we bear different degrees of responsibility depending on the different roles we play? Attributing responsibility is a tricky business. The reckless populist leader who tries to undermine the public health policies during a pandemic bears more responsibility for the resulting failures than his media-befuddled supporters (to pluck an example out of thin air, and, yes, this is the Covid-19 shoehorn bit. You were warned…) but they must bear some share of responsibility for putting him there in the first place.

One effect of the current crisis has been to bring to the fore the fact that our lives are deeply interdependent. Our daily lives are sustained by a vast complex scheme of social cooperation, stretching far beyond our borders, which goes largely unnoticed until parts of it stop functioning. We are responsible for our own contributions to this scheme, of course and when these are valuable we can take pride in them. But perhaps we are also complicit to some degree in sustaining of the more problematic patterns of interaction, those that damage the lives of others, whether through social and economic inequalities or environmental degradation. Being responsible, however, is not just a matter of looking back at the things we should have done differently, acknowledging the times when we should have resisted rather than complied, like Rein’s underground heroes. It is also a matter of looking forward, to the ways we can reshape our social relations.

The Greek historian, Polybius, believed that history moved in a circle. Human institutions were impermanent and when they were working well we could only hope to stave off decline for as long as possible before corruption set in. That was the bad news. The good news was that it was always possible, even when things looked most hopeless, that they might be set on the path to improvement. Whether we have grounds for cautious optimism about our future depends entirely on what we do next.

Bad Bridgets: Hear the true stories of notorious Irish girls and women who emigrated to North America in the hope of finding a new life, but went on to become thieves, kidnappers and even serial killers.#LoveQUB | #TrueCrime | #SSDGM @elaineffarrell @leannemcck

“The crisis is a tough time to think through all the pieces that are necessary.” That was an intriguing point by Bill Gates in his recent interview with Ezra Klein. It is a point that is too significant to escape the nose of a sober philosopher or the minds of persons who may be concerned about mental health or how to think in such a tough time. To contextualise Bill Gates’ statement here we may shorten it as “[it] is a tough time to think…”

Our major question is ‘how can or should we think when it is a tough time to think?’

There are other questions we may need to consider before we could derive an answer to our major question. Such questions include:

Bill Gates’ statement already answers the first question saying that there is a crisis that makes it tough to think. Almost everyone knows that something is wrong in the world at the moment. It is most likely that even babies in wombs could sense that a virus is currently wreaking severe havoc in the world that will soon host them. COVID-19 is making it a tough time to think.

Now that we know why it is a tough time to think we are left with the second question: How is it a tough time to think? This may not be straightforward to people who rightly think that the virus is not an infection of the brain or the nervous system, but rather an infection of the lungs. If it is not affecting the nervous system, so how does it affect thinking?

A recent article “Knowledge as the Working and Walking Narrative”, mentions that there are two basic processes of knowing which are called the Dual Carriageway of Knowing. On one way, the mind is working towards reality, the individual is directing herself (maybe by thinking) to acquire certain knowledge. On the other way, the reality is walking towards the mind, knowledge is entering the individual’s mind without the individual trying to acquire the knowledge. The individual is often in control of the former and the latter is often beyond the control of the individual. So how is this relevant?

During this challenging period, while we are trying to think about particular things and direct our minds to know somethings, our thoughts could be overwhelmed by the realities that flood our minds. It is almost impossible now for a day to go without news about Coronavirus. It is presently an overwhelming reality of everyday life and it creates a difficulty to concentrate on other things that we try to know. Social media and various outlets consistently flood our minds with the realities of COVID-19 even beyond what we would want to know. At the introductory phase of the virus, there were different descriptions from political leaders. For example, the President of China (Xi Jinping) calls the virus a “pneumonia epidemic”. The President of France (Emmanuel Macron) calls it “the invisible, elusive and advancing enemy”. The Prime Minister of Russia (Vladimir Putin) calls the virus a “common threat”. The (lucky) Prime Minister of the UK (Boris Johnson) calls it an “invisible killer” while the President of the US (Donald Trump) calls it “the Chinese virus”. These descriptions are followed by different statistics of deaths, of infections, disparities in infections and survival rates among other things. When these unavoidable torrents of information flood our minds, it is so difficult to concentrate on other aspects of life. It is indeed a tough time to think. Now, what can man do when it is tough to think?

It is not an option for a man to stop thinking because, as Michel Foucault puts it, “man is a thinking being”. Though it is tough to think, human beings must think. It is, however, important to be more thoughtful about thinking whenever it is tough to think because thinking often has a boomeranging effect. A religious personality once mentioned that “Man is a thinking being: what and how we think largely determines what we are and what we will become.” But our thinking will not only affect us as individuals; it also affects people around, specifically how we relate with them. So how can we be ‘thoughtful’ with our thinking when it is tough to think but we must think?

In 1637 the French philosopher René Descartes came up with Cogito ergo sum to argue for the attainment of certain knowledge. Cogito ergo sum means ‘I think therefore I am’. Bringing this Cartesian statement to context here, we may say that we can have a thoughtful approach to our thinking in tough times by starting the thinking with ourselves. We should make the ‘I’ come before the ‘think’. If we cannot avoid the influx of thoughts on Coronavirus, then we should personalise the thoughts. Let the thinking about Coronavirus starts with you:

What are the significances of the various thoughts on coronavirus for you as a person?

What are you identifying or knowing about yourself during the phase(s) of the virus?

Who do you think you are in the context of the coronavirus?

And what is the significance of who you are on others around you?

This is not a call for some irrational solipsism or untamed anthropocentrism. It is rather a call for a sincere self-examination. Despite all misgivings, the virus has presented humanity with a sober mirror to re-evaluate itself. Taking time before that mirror and painstakingly examining who we are individually is the best way to think now when it is difficult to think. Socrates rightly advised that “Man [and woman] know thyself. An unexamined life is not worth living.” Perhaps it is an advantage that the virus is offering us all the lockdown so we can pause and examine ourselves before we continue with the next phases of our lives. An example in this blog is the interesting article [https://blogs.qub.ac.uk/happ/2020/05/11/just-some-lockdown-thoughts/] by Rachel Thompson about how she recognised how less grateful she was for some benefits that she now realised that she is having. We should all take that bold stance to put up ourselves before the sober mirror of COVID-19 and check out who we really are, particularly in relations to others.

Many of us typically create a mental identity of being busy, we barely spend minutes with our families. We are now realising that we have only been using the workplace as an escape from the challenges at home. During the lockdown, we are now caught up with disagreements, misunderstandings and disputes that we have failed to address and have used our works as an excuse to avoid. Some of us believe that we are self-sufficient. We act, speak and think like we are the only ones existing in the world. We never believe we would need anyone in our lives but now we seek to communicate with people although virtually and we desire a reciprocal reaction from everyone. We are beginning to see that no one is an island, we are all social beings very much in need of ourselves. Some of us have enjoyed a lifestyle of discrimination, whether it is age, class, gender, language, race or what have you. We look down on certain people and implicitly or explicitly consider them as underprivileged. We think we are rich whereas health (not money) is the real wealth! We smile at peoples’ shabby dresses and feel satisfied that such people have already lost any competition with us for a good life. But who says life is a competition where the downfall of one is essential for the success of the other? Now the whole world is in a classroom, nature sombrely walked in as the teacher and slowly wrote the course title on the board: “COVID-19”. One of the learning outcomes is “That human beings will know that whether they are black, brown, yellow or white, they are all bloody humans. The only possible difference is that they can either be bad or good.”

Many of us are keen to have many things for ourselves notwithstanding if we need them or even to the detriment of those in dire need. Others consider us as greedy but it sounds derogatory and unacceptable to us. However, now we are learning that many of those things that we struggle to acquire are mere wants and not needs. Now that we can only pick three things per item at the stores and we still survive till another opportunity to leave the queue and enter the grocery stores; we are beginning to see that we have often used our wants to starve others of their needs. We now understand that what we really need in life is our health and the struggle to acquire more than needed is unhealthy. Now we agree with Immanuel Kant that, “we are not rich by what we possess but by what we can do without.”

There are some of us in positions of ‘power’ to make decisions about the success or failure of some persons under us. We forget that we are not the first and we will not be the last persons to occupy such a position. We happily, though surreptitiously, victimise or oppress those under us, we believe that it is the way to command respect. That is the way to show we are the boss. We sometimes boast that the promotion or success of certain persons is over our dead body. That is, as long as we are alive, such persons cannot have a promotion or some benefits that they deserve. Fortunately, we are now learning that the same air that keeps the victim alive also keeps the victimizer alive. And that a change can happen by tiny challenges in the puff of air we take in or out. We are all at the mercy of something above and beyond every one of us.

While we have been busy looking at our differences, nature is seeing us as one. Life, at least on earth, is similar for everybody. It is simply a journey from the womb to the tomb or from birth to death. We are part of each other and the best we can be is not about the best we can achieve but the best we can give to ourselves. There is a commonness in the humanness of our humanity which evolution may never be able to explain. We hear about death rates and we feel sorry even though it may be unlikely for us to be directly affected. But the empathy we show is a tacit admittance of the reality that anyone that goes out of existence is part of humanity, part of ourselves. And it is a sign that we too will go someday even if we become another Methuselah.

The COVID-19 period is like humanity is crawling through a dark long tunnel and unfortunately, many persons will not see the end of the tunnel. But it is not just about seeing the light at the end of the tunnel. It is about what you would look like when you get to the end of the tunnel. At the moment, humanity is acknowledging its frailty and there are many things that we cannot change. It is probably unhelpful to dwell much on what we cannot change at the expense of what we can and, even, ought to change. Take a bold step to assess yourself in the sober mirror and change what you ought to change while you still have the time. I will start to conclude with some apt lines by Shawn Carter (Jay-Z), in the song ‘Forever Young’: “So we live life like a video…when the [D]irector yells cut, I’ll be fine…” That you will be fine when the Director yells cut depends on you to now start thinking about yourself: Take a careful and reflective look at yourself in the mirror of life. Perhaps it is time to admit like Thomas Nashe (of blessed memory) that “Heaven is our heritage, Earth but a player’s stage” and agree with James Shirley that “Only the actions of the just, Smell sweet and blossom in their dust.”

Now that it is tough to think let the thinking starts with you!

Science is quite rightly seen as systematic and based on logic and reason. Counter-intuitively, a core tool used by scientists is the opposite: randomness,

Cause and effect

In order to identify cause and effect, scientists rely on the simple idea of random selection. Imagine that 100 patients are involved in a study I am conducting to figure out if a particular drug works. I write the names of the 100 people on small bits of paper and put them all in a hat. I close my eyes and pluck out one of the names. I do this again and again until I have 50 names. I call this group of 50 ‘the treatment group’. I give them the new drug that I wish to test. The other 50 people, still in the hat, are my ‘control’ group. I don’t give them the new drug.

After a while I see how my 100 patients are doing. If those in my treatment group are healthier than those in my control group I conclude that my drug works.

It’s all a tad more complicated than this, and computers have overtaken hats. But the basic logic is that via the use of non-reason (random allocation) we can achieve systematic results.

Prevalence

A second, and distinct, use of randomness is to try and figure out how widespread something is in the entire population of the country. For instance, what proportion of the whole population supports Manchester United? Or are happy with the government? Or have a particular disease?

This time a much bigger hat is needed. The name of everyone in the country goes into it on separate bits of paper. You put aside a few hours of your time. You close your eyes and pluck out, one by one, a thousand names. This 1000 are the people you wish to examine, either asking them questions in a survey or conducting a test of some sort on them. By simple virtue of the fact that they were randomly picked, they are a miniature version of the entire population. What we find out about this thousand will be true of the entire population (give or take a few percentage points). So, if 40 percent of our 1000 rather misguidedly support Manchester United, we will know that somewhere between 37 and 43 percent of the entire county will support Manchester United.

This information does not give us a strong handle on causation, it mainly describes how widespread something is. And it enables us to describe variation in prevalence: support for Manchester United is greater in the Manchester region than elsewhere and greatest among young males.

Randomly escaping Covid-19

Our response to Covid-19 crucially relies on these twin powers of random selection: understanding cause and describing prevalence.

The world is focusing on identifying an effective drug that causes us not to get the disease. A potential vaccine will only be declared effective if it passes the test of a randomly controlled trial, if patients randomly assigned to the treatment group show better health outcomes than those in the control group. All else is speculation.

As we await the development of an effective vaccine, we need to make policy decisions on how to regulate our social and economic behaviour. To relax human contact rules we need to have an accurate picture of how widespread the disease is in the population. We can’t examine every single human and so we take the shortcut of examining a random selection of several thousand. From the information from the several thousand we can paint a portrait of the entire country. From this information we can calculate whether it is wise to ease lockdown rules and allow more human contact, or whether doing so is likely to increase virus transmission to a level that places unsustainable pressure on the health service. The information can also inform how we may vary policy in different regions given the information about how prevalence varies in different geographical areas.

Beautiful contradication

How humans escape from Covid-19 will be the story of the collaboration of random and reason. Scientists, in both the natural and social sciences, leverage the simple notion of chance to generate knowledge. As we quite rightly seek logical reasons for the next steps we take in addressing the pandemic we may reflect on the fact that the reasoning will, very reasonably, be based on the anithesis of reason: randomness.

This post was originally published on QUB’s public engagement blog:

When lockdown was announced there were many things that I, and others like me, worried about – how to get groceries and medications, if my family would be safe, and what this would mean for my field work. One thing I did not worry about was how to get online. But more so than ever, we rely on the internet for all kinds of access. We use it for Covid-19 news and guidance, food delivery services, communication with families and friends, work and school. But not everyone has such easy access to the internet or the equipment needed to access it like smartphones, laptops and tablets. Without these things, lockdown causes further isolation and disadvantages.

This has become clear during my research with a women’s space that caters to asylum seekers and refugees here in Belfast. When lockdown began, I was impressed with the speed and agility with which the group adapted and moved online using Zoom. Not only have they continued to offer several regular classes, but they also expanded their offerings in response to the women’s requests and interests. Five days a week, women come together online to practice English, learn Chinese auto-massage, do yoga, or to cook together. And during these Zoom calls they also catch up and connect with one another. While these online activities could never fully replace in-person social activities, the women do feel they help them feel less alone and isolated. The problem is that while a core group of women do participate regularly, many more women do not have the technology or connectivity they need to participate.

Many women lack WiFi and the money to acquire it. That means they have limited opportunities to connect to the world outside their home. Before the lockdown, women would go to cafes, libraries and other public spaces with free WiFi for hours a day. That is no longer possible. And as a result, these women and their families are dramatically isolated from services, resources, friends and family. Children are home without access that would allow them to continue their education. Many also lack televisions, games, and other things we take for granted to keep ourselves entertained. Imagine being home with children for weeks on end, trying to keep them indoors but having nothing to keep them busy. On top of that, these women are separated from family members in other countries – unable to speak to husbands, children, mothers, etc. if they have no WiFi that makes regular calls affordable.

The problem of digital connectivity for marginalized populations is not new, but coronavirus has heightened the problem for the most vulnerable. Internet connectivity has become a necessity, especially during a prolonged lockdown.

Evening sunshine,

Empty street, I close my eyes,

Imbibing the warmth.

I’ve always been a walker. From being a well-exercised toddler with a mother who didn’t drive, I progressed to being teenager who furiously pounded the pavements before exams to handle the stress. My devotion to walking frequently saw me walking from my home in the South side of Dublin to my university on the North side, an ideal opportunity to listen to my favourite music (and save on bus fare).

I took a very cautious stance at the beginning of the lock-down, resolving to limit my exercise to my ancient treadmill. This didn’t last however, and before the first week had ended, I was back on the pavements, dashing out the door at the end of a day’s work after making the vital podcast/audiobook/music decision. In the intervening weeks, my evening walks have become increasingly important, allowing me to process my thoughts and stretch my legs after days that have become increasingly crowded, encompassing research, home-schooling and the sourcing of food and providing of frequent meals to a family and two pets with high standards.

Walking outside also serves as a reminder that, despite my present narrow horizons, the outside world still exists. Encountering another walker often involves a complex little dance incorporating a rapid appraisal of distance and strategic eye contact in order to go on your way. Occasionally, you may catch the other walker’s eye and ruefully smile, attempting cheeriness despite the changed reality.

This lockdown seems to pare everyday life down to its essentials – obtaining food takes more effort, there’s a new-found anxiety for the health of our loved ones and certainties about life, work, education and the future don’t seem so certain anymore. Sometimes old and simple pleasures help to remind us of who we are and where we came from in strange and unfriendly times.

My isolated experience thus far has given me a very inward focus on politics. Partially because my dissertation basis and degree program are inherently political, but also because of my emotional and personal desire to understand other people.

To be more in touch with the world, I have exposed myself to communities that I largely disagree with on civic duty, the role of government, collectivism, and what we consider to be fundamentally unnatural. These are all issues that have been latched onto while reconciling our current situation.

I’m really reaching here, but I think I can connect this to my dissertation using some philosophical acrobatics. For background, my thesis is focused on warlordism, and the role of ideological institutions in building military power. This has nothing to do with COVID-19 or what our daily challenges entail but I’m studying political science so let me have this.

However, in many ways, going through a pandemic has made me think more harmoniously with warlord ideology. Do I prioritize survival or the common good? What is the line that separates these two?

Life is predicated on unpredictability; we’ve known this since we were children. My primary deliberation now is how this present situation will affect us going forward. I feel that as a person who grew up with a comfortable life in a western country, this time is my ultimate confrontation with reality. The reality of death, contention, strife, and isolation.

I think that this whole experience has made me more cognizant of the subjects of my studies. In a paradoxically sociopathic and empathetic way, I better understand what it means to be a warlord. To watch the world collapsing around you, and to appear unwavering. To engorge yourself with as many human comforts possible, and sleep through the inevitable suffering of others.

Okay, full circle now, the point of my rum-fueled quasi-academic ramblings: I’m curious as to how this period of time will shape our future political ideology. Charles Tilly theorised that the development of our modern state system was artificially built through war, strife, and an intrinsic desire for domination, and now I wonder how we as a society will emerge from a day when the state very profoundly balances the scales of life and death. How will our society address an engrained polarization between inherent trust and obligatory defiance of what our leaders tell us to do? I know a lot of the latter is most vocally in America, trust me we’re not proud of it.

Thinking like a warlord, I am confronted with a societal afront that is nearly impossible to capitalize on. Any effort to gain power must be inadvertently humanitarian and done to alleviate harm. Perhaps we need a crisis to make those in power aware of what power entails. Some will argue that government impositions have made us “fascistic” to curb the liberties of individuals, others will say that stricter governments save more lives.

In any case, I am excited for the political dialogue to follow. I do not know how we will reconcile endemic socioeconomic issues with our confrontation with partial extinction, but I believe that this crisis will produce incredible ideologs; many of them selfish and narcissistic. People my age will later campaign for political office hailing their pandemic ideals and what they accomplished during “the Dark Time” of 2020.

There is a warlord in every person. My peers will scheme and conquer, some to support the state and others to bring it down. As a liberal arts major, I’m content to watch.

Death is our new currency. In the back of our minds there is voice that says, “I would kill to be free,” because freedom makes us powerful and dying is an inevitability. How do we teach ourselves about the common good, when goodness is a more nebulous concept than we have seen in out mortal lives?

These questions can’t be answered with science, political or otherwise, and none of us are qualified to give solutions. We will survive, in theory, perhaps in practice, because it is our nature rather than our duty to protect our fellow human beings. That is the warlord narrative that I would like to accept. A world without evil or vice would be fundamentally inhuman, and this crisis has provided me one of the most genuine human experiences that one could wish for.