It’s that dreaded time!

Except, I don’t feel as nearly as anxious as I probably should. To tell you the truth, my approach to every job interview up until this point has been to ‘wing it’. No preparation, all I needed to do was show up, smile, and suck up to the interviewer. It’s worked for me in the past, so can’t I just perpetuate the cycle of laziness and ‘wing it’ again?

Not this time.

Yes, I may have had a very basic idea of the interview process down through years of experience – ‘both parties should use the time to become acquainted, establish rapport, and explore whether employment would produce a suitable fit (Spence and Russel, 296). But this time, the stakes were a lot higher. I wasn’t going to get away with a last-minute attempt at charming the interviewers. I was going to be given thorough feedback, analysed, and put in the hot seat by my own coursemates!

And if there’s one thing you should know about Broadcast Production students, it’s that they’re seriously good at asking the questions you don’t want to hear. Those semesters spent chasing down MLAs for the perfect soundbite weren’t for nothing.

Preparation

Learners must selectively reflect on their experience in a critical way rather than take experience for granted and assume that the experience on its own is sufficient.

(Gibbs, 19)

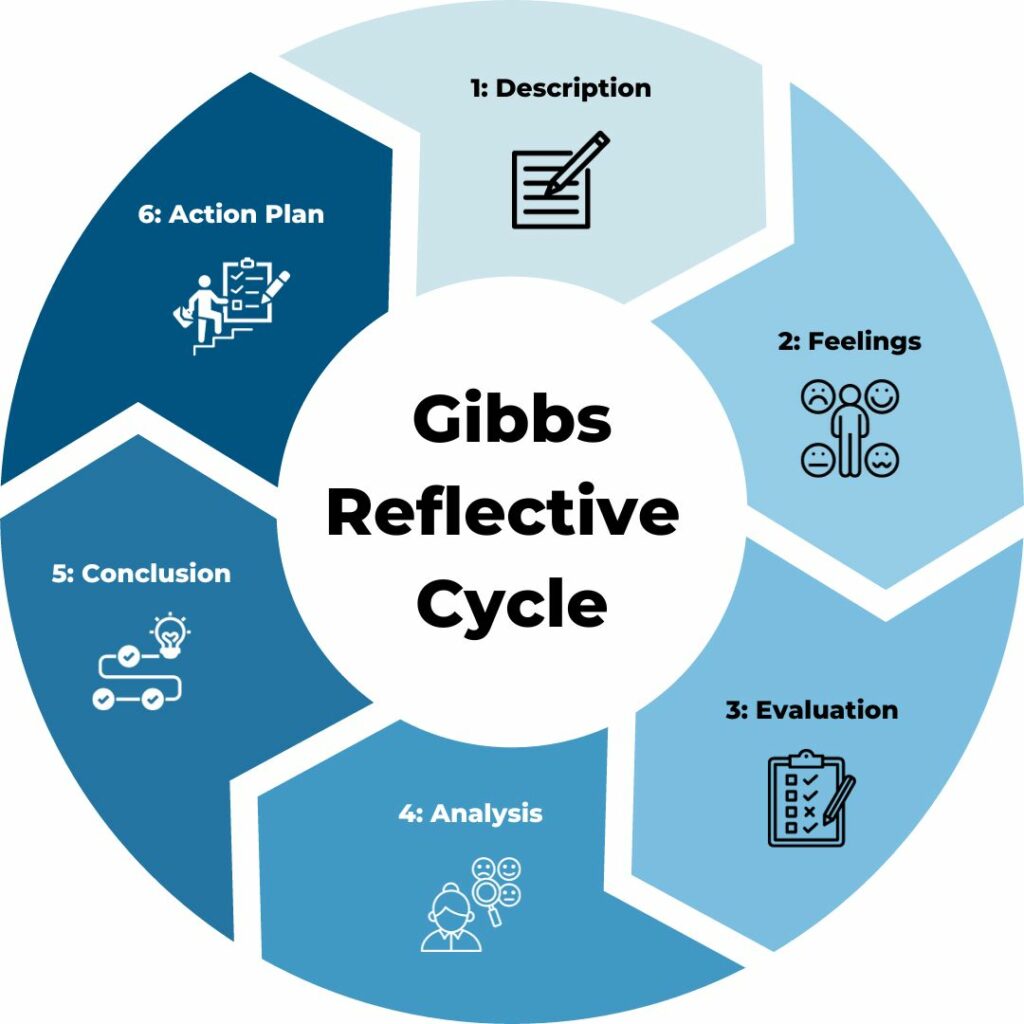

Having completed my simulated interview, I will be reflecting on the process using Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle (49). This model of reflection has allowed me to dissect and reminisce thoroughly about every stage of an activity in a critical and productive manner. Moreover, it has helped me to better understand where I am currently at, and where I need to go next.

If you’re anything like myself, it is painfully cringeworthy to have to replay some of your unsavoury moments and write them down! However, this is an uncomfortable space we all must get used to. Jasper put it best: ‘We need to be willing to revisit our own actions, and we need to have some insight into ourselves. We also need to be able to accept responsibility for our own actions and the choices we make (20). It’s about time I told you about the choices I made, and the choices I’m going to make in the future.

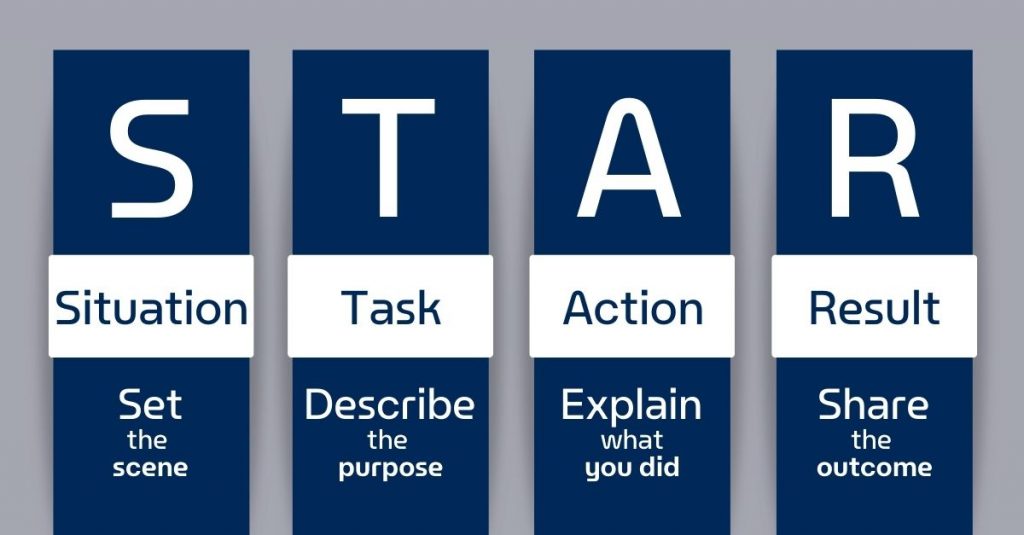

Going into the process, I looked carefully at the STAR method for providing interview answers (“The STAR Method.”), fully knowing that I’d be quizzed about how I handled a tricky situation. I decided to provide an example from outside my usual area of media and television by speaking about a challenge I encountered while volunteering with Sólás Special Needs Charity on a Summer Scheme in South Belfast.

Situation: As Summer Scheme volunteers and attendees are split into groups, children take turns heading out on special day trips. I was assigned to a group of older kids for indoor playtime. Suddenly, a staff member from the other group appeared and announced they were short-staffed for the beach trip.

Task: The staff member from the other group needed an extra pair of hands to look after the smaller children whilst at the beach in case they got overstimulated or ran away.

Action: I was unfamiliar with this group of younger children, but I volunteered to help the beach group that day in order for the trip to go ahead safely.

Result: I was paired with a lovely boy who was in need of a playmate and was his ‘buddy’ for the day. I also kept an eye on other children where possible, and the trip went smoothly.

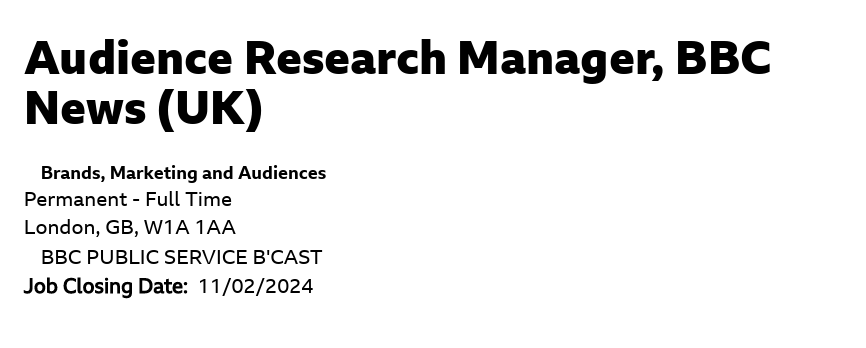

My chosen job role for the Simulated Interviews was that of an Audience Research Manager for BBC News. Following the guidance of Branmar, I built a comprehensive understanding of the role through studying the specification and learning about what situations I would potentially encounter in this type of job (Branmar). I have had the privilege of having completed a Research Internship before, so with my combined past experience and newfound knowledge about the company, I found some overlap and knew I could speak in detail about specific requirements and how I could meet them – for example, having experience using BARB as a tool for audience viewing figures, creating spreadsheets and reports.

Additionally, I prepared for the interview by asking myself what I liked about the job and the work I was (hopefully) going to do (Spiropoulos, 68). Again, I reminisced about my prior experiences and studied the role specifications. I deduced that a large portion of my enjoyment for such work stemmed from a passion for knowledge and innovation, paired with a desire to deliver and excel audience expectations – this could all be achieved through the magic of audience research.

Reflection

Combining the feedback I received with my overall experience, I present to you my reflection using Gibb’s Cycle.

Description

On the day of the interview, we were sorted into smaller groups. My group consisted of peers I knew well, and I volunteered to be the first interviewed. I handed them my job specifications and waited outside until I was invited back in for questioning. I introduced myself and shook their hands, then sat down.

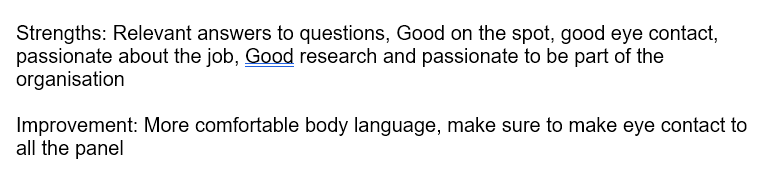

I was asked a series of questions about my abilities, interests, and people-based skills by all three of my panellists. I did my best to listen carefully, paying attention to certain phrases (Roderick and Lucks, 48). The interview was timed and came to a little under ten minutes. We exchanged our final pleasantries and I returned outside as the interviewers filled in the feedback form. Upon retrieving the feedback, the responses were mostly positive, with my primary area of improvement being my overall body language .

Feelings

In the days and hours leading up to the activity, I felt relatively calm and confident about my performance, having prepared some answers and my job specification.

When my time finally came, however, I felt an onset of nerves as I realised it was actually happening! I worried about whether or not I had prepared sufficiently, but knew I had to go ahead with it regardless. I was ready to demonstrate my knowledge pertaining to the role, so I reassured myself before I was called in. Afterwards, I had mixed feelings about my attempt – I did some parts well, others I felt not so much – but I believe it went better than I thought it would.

Evaluation

As mentioned prior, my strengths certainly laid in my ability to demonstrate a clear passion and knowledge pertaining to my desired job. This was mirrored in my feedback form. I also knew to make use of the STAR method and a few answers I prepared, speaking about what I learnt while volunteering, on the course, and during my brief internship.

As for my weaknesses, they stemmed entirely from my body language and facial expressions. At the time, I was entirely unaware of my own habits and was slightly disappointed that I did not seem to catch this. Nonetheless, I am glad that this was highlighted.

Analysis

Assessing my performance, I know clearly where my strengths and weaknesses lie. I can observe that my positive attributes come from my genuine interest and preparation for the role. On the flip-side, I reviewed my notes on body language and eye contact and came to a revelation about a trait of mine I had overlooked for years – in truth, I had a habit of ‘staring into the sky’ whilst thinking on the spot about my response. A memory flashed of when this happened to me during a Spanish oral assessment in secondary school, and my teacher pointed it out. Unknowingly, I had repeated this habit in front of my interviewers, and thus gave the appearance of not making proper eye contact with certain panellists. It was unintentional, but a careless mistake that has thankfully been brought to my attention as a definite area of improvement.

Conclusion

To conclude, there are components of my interview and communication skills that I now feel require special attention – especially my body language, appearance, and structure of responses. Other skills that I displayed were recognised – demonstrated knowledge/experience, research and passion. These are components I intend to continue strengthening in conjunction with those I must practice further.

Action Plan

The most important part of any model and reflection is the action plan, or ‘Now what?’ step at the end. Without this, the reflection is just telling a story with no useful, identified development or progress.

(Stonehouse, 2)

My plan of action for future job interviews is to improve upon my body language, eye contact, and response time by conducting my own simulated interviews at home. I could do this with a trusted peer or family member, and record myself while doing so. Afterwards, I can rewatch the video recording and make notes on my performance – by watching myself, I become more aware of my own habits and what to implement/be mindful of when in action.

Furthermore, I intend to increase the level of research I put into the job role, company, and also interview skills overall. By referring to tips found in books such as the You’re Hired series, I can train myself on what professional interviewers expect of me, and what I can expect in return.

By combining reading, research, and physical practice, I will become more accustomed and ready for future interviews in the media industry after I graduate.

Final Thoughts

Overall, I’m rather pleased with the outcome and process of the Simulated Interviews! What I initially viewed as another tedious hurdle to climb has become a valuable learning experience for me. Despite my hiccups, I am grateful for the opportunity and have learnt more about myself and my peers. Having reflected on my individual performance, I can carry onwards with a newfound confidence in the abilities I have and the abilities I will acquire through proper practice and patience.

Works Cited

Brammar, Laura. “Interview Skills.” BMJ (Online), 2008, p. cf_bral_interview_22-, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1078.

Gibbs, Graham. Learning by Doing. Oxford Further Education Unit, 1988.

Jasper, Melanie. Beginning reflective practice, 2nd edition. Cengage Learning EMEA, 2013.

Roderick, Ceri, and Stephan Lucks. You’re Hired! : Interview Answers : Impressive Answers to Tough Questions. Trotman, 2010.

Spence, Brian, and Amy Russell. “Using Mock Interviews to Improve Students’ Resume and Interview Skills.” Radiologic Technology, vol. 94, no. 4, 2023, pp. 296–98.

Spiropoulos, Michael. Interview Skills That Win the Job: Simple Techniques for Answering All the Tough Questions. Allen & Unwin, 2006.

Stonehouse, David. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants, vol. 14, no. 11, 2 Dec. 2020, pp. 572–574, doi:10.12968/bjha.2020.14.11.572.

“The STAR Method.” The STAR Method | National Careers Service, nationalcareers.service.gov.uk/careers-advice/interview-advice/the-star-method.