A reflection on my simulated interview

Interviews 101

My Limited Experience

The initial prospect of partaking in stimulated interviews was extremely daunting, having never experienced an interview for an industry job before. The territory wasn’t entirely unfamiliar to me, however, having successfully completed half a dozen interviews for part-time posts in the service industry over the past six years. These experiences helped me feel confident with interview etiquette, as well as how to present myself to prospective employers.

Before commencing my role at Arts Care as part of the AEL placement module, I did not undergo a formal interview process. I met the staff from the Communications department at a placement providers’ event organised by Queen’s and, from there, we arranged an informal ‘talk’ to discuss my potential role within the organisation. Although this experience improved my networking skills, the absence of an interview stage meant I was unable to build upon my interview performance, which increased my anxiety for the upcoming simulated interview.

However, given the cruciality of interviews within the world of work, I was eager to build upon my previous experience. Naim et al (2016, 191) summarise the significance of the interview process in the following quote:

JOB INTERVIEWS ARE UBIQUITOUS AND PLAY INEVITABLE AND IMPORTANT ROLES IN OUR LIFE AND CAREER.

Despite many crew members in the film industry finding work through connections and recommendations from previous co-workers, the interview process in film for new first-time employees cannot be understated. Blair, Grey and Randle (2001) found that:

35 PER CENT [OF CANDIDATES] GOT THEIR FIRST JOB THROUGH AN INTERVIEW

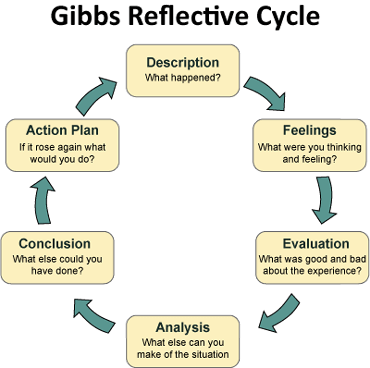

In this blog post, I will be reflecting on my simulated experience using Gibb’s reflective model (1988, Figure 1).

Preparing for the Interview

Finding a job that fits me

For my simulated interview, I was tasked with selecting a job listing that I could potentially apply for in the future. I found the process of choosing a listing easier than I anticipated, with my preferences being a job that:

- I could transfer the skills I have acquired throughout my degree and placement

- I had the opportunity to learn new skills, building upon my experience and my portfolio.

Specifically, I knew I wanted to hone the photography skills I have accumulated throughout my placement with Arts Care. Additionally, I aimed to advance my photography to incorporate more than event photography and cinematography. For these reasons, I chose a Freelance Property Photography and Event Management post advertised on Indeed (and linked below).

Northern Ireland has many openings for property photography as it is a service that is constantly required. I felt it seemed like a viable future career option due to the demand for property photography from estate and letting agencies.

As aforementioned, I have prior experience in event photography (through my placement), portrait photography (in my free time), and cinematography (through being the director of photography in two films through my education). I selected the above listing to hone my skills in property photography to diversify my portfolio.

My appeal was not only limited to the photography element of the job listing, but additionally the event management role. In several student film projects, I have undertaken a producer role and gravitate towards both organisational and creative posts within film. I was attracted to this role in Property Management and Event Management as it met the criteria of what I was searching for in a potential job: it would allow me to showcase my pre-existing skills, as well as build new ones.

The Interview Process

And my anxiety surrounding it

Before the simulated interview, my peers and I sent our job listings to each other so that we could prepare questions for each specific job we had chosen, allowing us to more accurately replicate the ‘real thing’.

Many aspects of the interview were daunting, paramountly, how my nerves may impede my performance. Unfortunately, I am a very anxious person, particularly in high-pressure and social experiences. I was aware of anxiety’s negative impact on success after the interview stage as Powell, Stanley and Brown (2018, 195) found that:

SEVERAL STUDIES HAVE SHOWN A NEGATIVE RELATION BETWEEN INTERVIEW ANXIETY AND INTERVIEW PERFORMANCE, WHICH MEANS THAT ANXIOUS CANDIDATES ARE LESS LIKELY TO GET JOBS.

Thankfully, during the interview, my anxiety was lessened by being interviewed by my peers, whom I felt comfortable with, as well the interview occurring in a familiar environment. In addition, my own efforts helped to alleviate pressure: by putting a lot of time into preparation for the interview and studying the job listing inside-out, I went into the interview as confident as possible, with the knowledge that I had answers for any questions they could possibly ask.

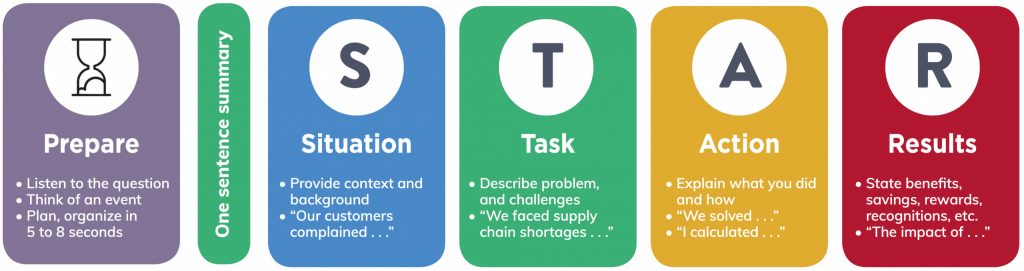

During the interview, I utilised the ‘S.T.A.R.’ technique (figure 2) when answering questions to arrive at clear and concise conclusions which proved my ability to problem solve and resolve conflict. I used examples from my professional and academic careers to showcase these skills.

Overall, the interview itself was an incredibly positive experience that helped me overcome the interview-related anxiety I have been struggling with my entire professional life. However, in the moment, I forgot simple pleasantries, which often go a long way in interviews, such as introducing myself properly and shaking the interviewers’ hands. The simulated interview process was a huge learning experience for me and extremely beneficial, providing a unique opportunity to improve interview technique in a controlled environment.

Feedback

The Moment of Truth

Upon completion of my simulated interview, my peers/interviewers were asked to fill out a feedback form. The importance of feedback at the end of the interview process cannot be understated, with Williams (2008, 2) posing the question:

CANDIDATES WITH MORE INTERVIEW EXPERIENCE MIGHT PERFORM BETTER THAN NOVICE INTERVIEWEES. BUT DOES PRACTICE ALONE IMPROVE INTERVIEW SKILLS, OR DO CANDIDATES NEED SOME TYPE OF FEEDBACK OR COACHING IN ORDER TO RECOGNIZE AND IMPROVE SKILL DEFICIENCIES?

Williams goes on to determine that feedback and coaching do, in fact, improve candidates’ interview skills by providing them with aspects of their performance that require improvement. For this reason, I was eager to read my peers’ feedback. The entire simulated interview was a huge learning experience for me, and although I felt confident with my performance in the interview, I was keen to read about the experience from the interviewers’ point of view.

Content

When asked to critique the content of my interview, my peers wrote that my ‘answers were clear and relevant to questions’ with a ‘good explanation of photography skills and experience’. I attribute these clear responses to my utilisation of the S.T.A.R. interview technique (as explained in ‘The Interview Process’ chapter), which allowed me to stay focused on the questions being asked, without going on unrelated tangents (which I am usually quite prone to do!). They also commented that I had a ‘good use of industry language’. This felt very reassuring to me as I had successfully communicated my understanding of the industry, and used my education to demonstrate this.

Reflection

In the reflection section of my feedback form, the interviewers wrote that my ‘reflection was suited for the job’ and demonstrated my ‘knowledge and experience through [my] employment, projects and work.’ I was also thrilled with this response, relieved that I had successfully articulated my relevant experience which made me a good candidate for this job listing.

Presentation

As aforementioned, I commenced the interview process with anxiety about how my nervous disposition may impede my performance. Despite my efforts to appear more confident in the preparation process, I still feared that my anxiety may have impacted my interview. Therefore, I was pleasantly surprised when I read that under the presentation section of my feedback, the interviewers had commented that I maintained ‘good eye contact and confident body language’ with a ‘steady pace’. It was ecstatic that my huge efforts to present myself more confidently had paid off, and I will be using a similar preparation tactic for future interviews.

Although the feedback was helpful in identifying my strengths as an interviewee, I wish I had asked my peers to be brutally honest with their critiques of my performance. I understand why they did not write any negative feedback on the feedback form, perhaps out of fear of appearing mean-spirited or hurting my feelings. However, I feel negative criticism is equally as important as positive, and wish I had asked them to include both so I could use this experience to identify and hopefully amend the weaker aspects of my interview.

Overall Experience

Conclusively, the experience of completing a simulated interview, though initially anxiety-inducing, was overall very positive and beneficial for future industry interviews. It not only helped me build upon my interview technique, but also alleviated much of my anxiety surrounding the interview process, offering an invaluable insight into the world of work.

Bibliography

Blair, H., Grey, S. and Randle, K., 2001. Working in film–employment in a project based industry. Personnel review, 30 (2), pp.170-185.

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. Oxford: Oxford Further Education Unit.

Naim, Iftekhar, Md Iftekhar Tanveer, Daniel Gildea, and Mohammed Ehsan Hoque. “Automated analysis and prediction of job interview performance.” IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 9, no. 2 (2016): 191

Powell, D.M., Stanley, D.J. and Brown, K.N., 2018. Meta-analysis of the relation between interview anxiety and interview performance. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 50(4), p.195.

Williams, K.Z., 2008. Effects of practice and feedback on interview performance (Doctoral dissertation, Clemson University). 2