AEL3001 Work-based Learning Blog 2

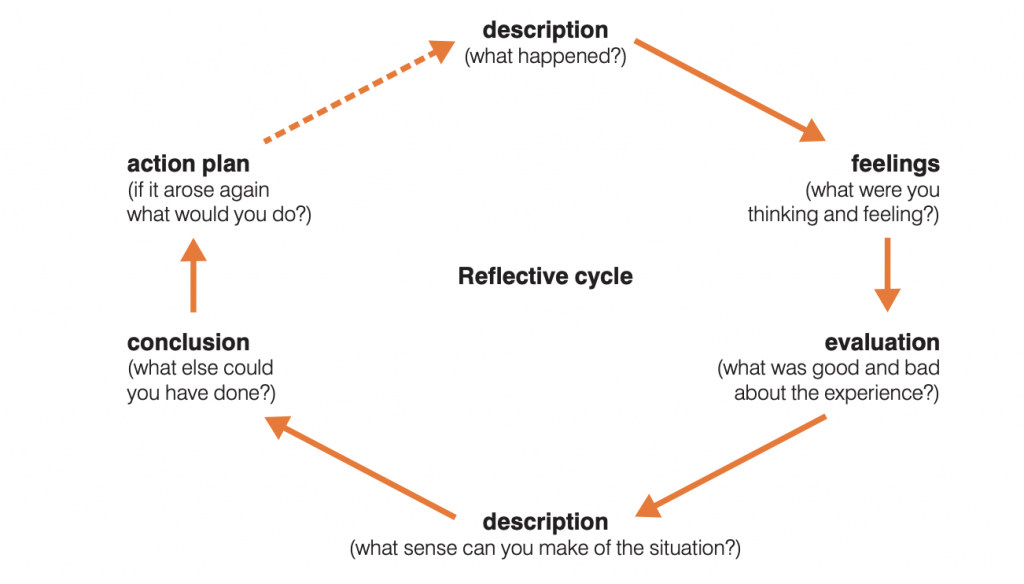

In this blog, I will use Gibbs’ reflective cycle as a guide whilst outlining my reflective writing surrounding my experience of the simulated interviews that occurred in Semester 2 week 3. There are six stages to Gibbs’ model that each pose a question, see the image below (Gibbs, 1988).

It is important to reflect on a new experience and through it we often learn something new about ourselves or the experience we are reflecting on. Author Moon sums this up well: “Reflection as a process, seems to lie somewhere around the notion of learning and thinking. We reflect in order to learn something, or we learn as a result of reflecting” (Moon, 2004).

My experience of the simulated interviews in week 3 can be summed up as positive, beneficial, and encouraging. I was in a group with Anna, Emma, and Emily and we rotationally took on the roles of interviewers and interviewees. All the interviews followed this format: the interviewee waited until the interview panel decided on which questions to ask them, and when they returned the questions were asked and they provided an answer for each. Following the short 10-minute interview the panel discussed feedback for the interviewee, which included a healthy balance of positive affirmations and constructive criticism. Emma and Anna both aspire to be secondary school music teachers and similarly, Emily and I both dream of being audio engineers which served as an advantage for our group. During the interviews, one of us knew what the job entailed and had the terminology knowledge that the others did not possess. The role of an audio engineer can be described as “a key figure in the reproduction, recording and facilitation of sound” (Rutter, 2011).

Throughout the interview process, whenever an answer was along the right lines but did not provide enough detail, as a team of interviewers we communicated and adapted accordingly by probing the interviewee to develop their answer. As this was an informal exercise, we could help each other make the most of the opportunity which improved our learning. We did our best to aid the interviewee’s anxiety or nervousness if they appeared to have any since we wanted them to grow in self-confidence and their ability to cope with stress. Equally, for me, when playing the interviewer role, I felt slightly nervous, and I worried that the questions I asked were not realistic and too simple. Interviews can be very stressful, and some people are better at coping with their stress than others, I have been told in the past that I don’t appear stressed even though I know at the time I was. Although I may not outwardly appear stressed, I know I need to develop my stress-coping skills inwardly to help myself overcome the debilitating impacts of being stressed. Stress can impact my interview answers which could consequently impact my success in the rest of the interview process.

Reflecting on the feedback we gave each other; we were honest with it and did not fall into the trap of simply providing positive remarks. We gave well-rounded feedback and at the same time avoided being needlessly critical. This was very helpful, and I believe fulfilled the intended purpose of the simulated interviews; to enhance each other’s confidence in their strengths but equally to identify any nervous twitches and mistakes which need to be worked on. The feedback I received from the rest of the group on my interview performance was interesting to hear as others can see how you perform better than you can. The group collectively told me I was good at providing examples and I was confident in my delivery, however, next time I should think about including more detail and expanding my answers further to elongate my responses. I kept good eye contact throughout the interview which is important, and it persuades the interviewer you are a good communicator.

The simulated interviews allowed me to grow in teamwork skills with others I had not worked in a team with before. Communication between a team of interviewers is vital for the interview to run smoothly and within a business model in general. I gained a glimpse of the organisational culture, policies, and processes that go into an interview and their importance despite the simulated interviews being a very modest version of a real interview. Additionally, I developed my confidence in interacting in an interview directly about my dream career. I have not yet had any experience of a job interview for a position directly related to my degree. Although this was simply a simulated exercise, it helped me think seriously about how I would answer questions in a real job interview for an audio engineer position or something similar and act out the practice of it. The experience of the simulated interviews has reminded me that an interview for my future career could commence very soon as I look ahead to graduating in a few short months! The prospect of leaving Queen’s and entering this new phase of my life post-university is daunting, however, I am glad that I have had this experience of simulated interviews from an interviewee and interviewer perspective. It has helped me to see interviews from a different point of view which will ease my nervousness when it comes time to perform a real-life one. “Job security in the music industry; volatile, shifting markets, new media trends and fickle audiences can render certain job roles defunct in a very short space of time” (Rutter, 2011). This quote from Rutter’s handbook is quite blunt, however, it touches on the well-known issue of job security, all the more reason to improve my interview skills.

My work placement has allowed me to become familiar with the inner workings of an audio-visual company. This has escalated my understanding of the day-to-day reality of being an audio engineer as I have observed the team on my placement, giving me a piece of practical knowledge to go hand-in-hand with my theoretical knowledge from Queen’s. Each performance Belfast Community Gospel Choir has done has varied slightly even if the setlist is similar there have repeatedly been variations in the setup, sound, and level of audience interaction. This is mainly due to differences in the venues and their PA systems, although the team at my work placement company Third Source is very experienced and they have been working with BCGC since its beginnings in 2009. Concerning the simulated interviews, I was able to include the newfound knowledge I have developed since starting my work placement in my answers, providing a wealth of experience to talk about when I was asked about my experience in the field. However, if I could do it again, I would expand on what I said about these experiences and be more detailed to enrich my responses.

According to Jay Juchniewicz, the following traits are important for music teachers to possess: “enthusiasm, strong communication skills…strong teaching skills, caring, and knowledge of subject matter” (Juchniewicz, 2016). These key characteristics may appear unimportant as a list on a page but in reality, they are vital for teachers to possess. As I reflect on my school days and in particular on my music teachers, I understand the significance of these attributes. Especially “caring” since music teachers catch a glimpse of their pupils’ musical talents right from the beginning and help to nurture them. Consequently, this early development greatly impacts the pupil’s success in music and their attitude towards it. Reflecting on the simulated interviews, I can confidently say that both Anna and Emma appeared to have these characteristics through their personalities but equally in their answers to the questions.

For audio engineers “one of the keys to a successful engineering career is to balance creativity with performing the tasks that one is contracted to perform” (Macaluso, 2009). An audio engineer’s role is often devalued by the music industry where the artist is elevated to centre stage both metaphorically and literally. The importance of the audio engineer’s skillset is seen as insignificant compared to the talent seeping from the artist. In a world where credit is rarely given to the producer of a song and instead to the voices that sing it, it is challenging for audio engineers to highlight their talent when all eyes are fixated on the performers. More often than not the performers do not have much input in the songs they have in their albums since songwriters and engineers tend to be given the job of creating these masterpieces. This feeds the fire of the illusion to fans all the more that their musical icons do write their material themselves. However, there are many examples of artists who genuinely do partake in all the elements of the creative process and even lead up the production of them, but they are usually more experienced in their field.

In conclusion, the simulated interviews taught me a lot about myself and how to improve my responses in interviews. I will take on board the feedback from my peers and apply it in the future when I face a real job interview.

Word count: 1515

References:

Gibbs, G., 1988. Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. Oxford: Oxford Further Education Unit.

Jackson, B.M., 2015. The Music producer’s survival stories: interviews with veteran, independent, and electronic music professionals. Boston: Cengage Learning

Juchniewicz, J., 2016. An examination of music teacher job interview questions. Journal of Music Teacher Education.

Macaluso, S.J., 2009. The Business of Audio Engineering. Music Reference Services Quarterly.

Moon, J.A., 2004. A handbook of reflective and experiential learning: theory and practice. London: Routledge.

Rutter, P., 2011. The Music Industry Handbook. London: Perlego.

Zager, M. (2012) Music production: for producers, composers, arrangers, and students. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. 2nd edn.