/*! elementor – v3.19.0 – 07-02-2024 */

.elementor-widget-image{text-align:center}.elementor-widget-image a{display:inline-block}.elementor-widget-image a img[src$=”.svg”]{width:48px}.elementor-widget-image img{vertical-align:middle;display:inline-block}

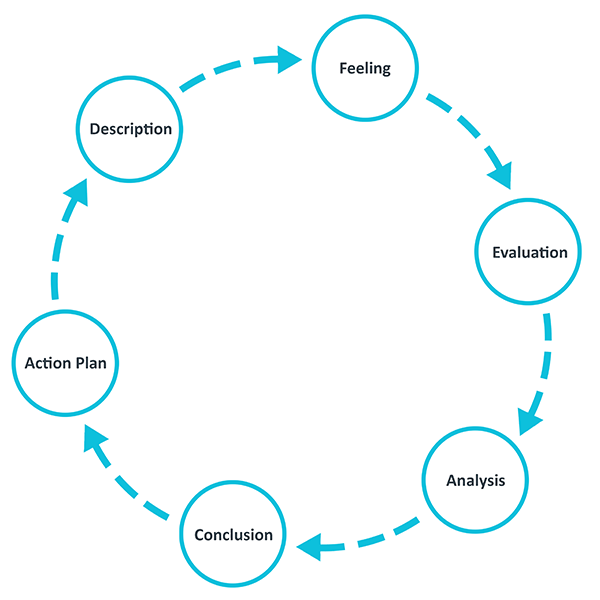

Every student knows the familiar sting of bias in the classroom. Whether it is the teacher’s pet who conveniently disappears for ‘messages’, or the diligent student who devours every recommended reading list, it is evident that favouritism plays a role in education. We have all observed the students who seem to have an excellent rapport with their teachers who effortlessly earn higher marks for their work. As a student, I often found myself envious of their seemingly privileged status, harbouring a hint of annoyance towards the teachers who clearly favoured them. Little did I anticipate that I would one day find myself on the other side of this dynamic, caught in the web of bias during a crucial assessment. In this blog post, I will delve into my personal experience using Gibbs’ six-step reflective cycle. Through analysis and evaluation, I will explore how I handled my bias, the steps I took to address this challenge, and the profound lessons I have gathered from this experience.

/*! elementor – v3.19.0 – 07-02-2024 */

.elementor-widget-divider{–divider-border-style:none;–divider-border-width:1px;–divider-color:#0c0d0e;–divider-icon-size:20px;–divider-element-spacing:10px;–divider-pattern-height:24px;–divider-pattern-size:20px;–divider-pattern-url:none;–divider-pattern-repeat:repeat-x}.elementor-widget-divider .elementor-divider{display:flex}.elementor-widget-divider .elementor-divider__text{font-size:15px;line-height:1;max-width:95%}.elementor-widget-divider .elementor-divider__element{margin:0 var(–divider-element-spacing);flex-shrink:0}.elementor-widget-divider .elementor-icon{font-size:var(–divider-icon-size)}.elementor-widget-divider .elementor-divider-separator{display:flex;margin:0;direction:ltr}.elementor-widget-divider–view-line_icon .elementor-divider-separator,.elementor-widget-divider–view-line_text .elementor-divider-separator{align-items:center}.elementor-widget-divider–view-line_icon .elementor-divider-separator:after,.elementor-widget-divider–view-line_icon .elementor-divider-separator:before,.elementor-widget-divider–view-line_text .elementor-divider-separator:after,.elementor-widget-divider–view-line_text .elementor-divider-separator:before{display:block;content:””;border-block-end:0;flex-grow:1;border-block-start:var(–divider-border-width) var(–divider-border-style) var(–divider-color)}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-left .elementor-divider .elementor-divider-separator>.elementor-divider__svg:first-of-type{flex-grow:0;flex-shrink:100}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-left .elementor-divider-separator:before{content:none}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-left .elementor-divider__element{margin-left:0}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-right .elementor-divider .elementor-divider-separator>.elementor-divider__svg:last-of-type{flex-grow:0;flex-shrink:100}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-right .elementor-divider-separator:after{content:none}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-right .elementor-divider__element{margin-right:0}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-start .elementor-divider .elementor-divider-separator>.elementor-divider__svg:first-of-type{flex-grow:0;flex-shrink:100}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-start .elementor-divider-separator:before{content:none}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-start .elementor-divider__element{margin-inline-start:0}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-end .elementor-divider .elementor-divider-separator>.elementor-divider__svg:last-of-type{flex-grow:0;flex-shrink:100}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-end .elementor-divider-separator:after{content:none}.elementor-widget-divider–element-align-end .elementor-divider__element{margin-inline-end:0}.elementor-widget-divider:not(.elementor-widget-divider–view-line_text):not(.elementor-widget-divider–view-line_icon) .elementor-divider-separator{border-block-start:var(–divider-border-width) var(–divider-border-style) var(–divider-color)}.elementor-widget-divider–separator-type-pattern{–divider-border-style:none}.elementor-widget-divider–separator-type-pattern.elementor-widget-divider–view-line .elementor-divider-separator,.elementor-widget-divider–separator-type-pattern:not(.elementor-widget-divider–view-line) .elementor-divider-separator:after,.elementor-widget-divider–separator-type-pattern:not(.elementor-widget-divider–view-line) .elementor-divider-separator:before,.elementor-widget-divider–separator-type-pattern:not([class*=elementor-widget-divider–view]) .elementor-divider-separator{width:100%;min-height:var(–divider-pattern-height);-webkit-mask-size:var(–divider-pattern-size) 100%;mask-size:var(–divider-pattern-size) 100%;-webkit-mask-repeat:var(–divider-pattern-repeat);mask-repeat:var(–divider-pattern-repeat);background-color:var(–divider-color);-webkit-mask-image:var(–divider-pattern-url);mask-image:var(–divider-pattern-url)}.elementor-widget-divider–no-spacing{–divider-pattern-size:auto}.elementor-widget-divider–bg-round{–divider-pattern-repeat:round}.rtl .elementor-widget-divider .elementor-divider__text{direction:rtl}.e-con-inner>.elementor-widget-divider,.e-con>.elementor-widget-divider{width:var(–container-widget-width,100%);–flex-grow:var(–container-widget-flex-grow)}

/*! elementor – v3.19.0 – 07-02-2024 */

.elementor-heading-title{padding:0;margin:0;line-height:1}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title[class*=elementor-size-]>a{color:inherit;font-size:inherit;line-height:inherit}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-small{font-size:15px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-medium{font-size:19px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-large{font-size:29px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-xl{font-size:39px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-xxl{font-size:59px}

Well, what happened?

As my one hundred hours of placement as a Drama assistant teacher at St. Malachy’s College Belfast ended, and exam season approached for both myself – a university student – and the GCSE pupils. I reflected on the anxiety and terror that once consumed me as I performed my year twelve final scripted piece. The scripted piece constitutes thirty-five percent of a student’s GCSE Drama grade. So, the determination and drive the pupils had when they selected a theatrical piece, that allowed them to excel at their highest potential, was evident. The boys in year twelve selected pieces from Punk Rock, The 39 Steps and 1 Man 2 Governors – all of these works I have interacted with throughout my time as a Drama student. Miss Hughes, my placement teacher and head of the Drama department at the College, was delighted with my previous engagement with these pieces and asked if I would assist the students in their preparation for their final performance. I gladly aided the pupils with creative suggestions and guided them through their performance objectives, and outcomes in line with CCEA’s mark scheme.

After the midterm break on the first Monday back to school routine, it was their moderation day and all three groups had to perform their pieces to be graded. Miss Hughes asked if I could aid her in marking the students as she required multiple assessors to ensure there was no confirmation bias. Ultimately, her worry of integrity was my reality as I had watched the students select their pieces, helped them come to life and assisted them when they asked for my input of performance ideas. I had built a great rapport with the class and became attached to their pieces and performances through their dedication and exceptional talent throughout the rehearsal process. One of the most poignant challenges I faced when assisting Miss Hughes with her marking for the final performances, was navigating the intricate balance between the objective assessment and my subjective emotions. This challenge was vividly illustrated during an incident with one of the top candidate students. This student, who had been predicted a top band grade of an A, consistently demonstrated their exceptional talent and dedication to their performance within their class rehearsals that I aided.

However, during their final performance for examination they fell short of their anticipated standard, due to nerves and a forgotten line which threw them off. It was evident to both Miss Hughes and I that the student’s final performance did not represent their potential, as demonstrated in earlier rehearsals and classwork. Yet, the mark scheme and examination guidance provided by CCEA required us to assess their performance based on what transpired during the final exam. The student’s final performance yielded a lower band grade, placing them at an B instead of an A.

How did you feel?

As a witness to the student’s commitment to their piece and progress throughout their rehearsals, as well as an active participant in their assessment, I could not help but feel a profound sense of disappointment for the situation and sadness for the pupil. When they initially forgot their line, I felt my heart drop to my stomach and a shortness of breath as they broke character as scrambled for a prompt to continue. A slight sense of relief came over me when the student was able to finish the scene after this slip-up, however I became disheartened as the piece ended as I was aware that their examined performance was not on power with prior rehearsals. The discrepancy between what I witnessed during previous preparations and the underwhelming final performance was disheartening. Witnessing a student falter in the critical moment, after watching their dedication and talent in class, was a bitter pill to swallow. I felt internally conflicted, and I found myself grappling with weight of decision making when it came to the grading the student. I felt compelled to give them the benefit of the doubt and place them in a the top band. I knew I was not alone in this feeling, as Miss Hughes also expressed her disappointment and frustration. However, I felt slightly ashamed and guilty as I became aware that I might be biased in my marking of the student, as I thought about the pupil’s subjective potential and not their objective actual output. At some points in the grading process, I found it emotionally challenging to detach myself from the great student-teacher rapport I had built. I recognised that my bias attitude came from a place of empathy as I remembered the impact grades have on my academic journey and self-esteem, particularly in Drama…

I told Miss Hughes that I was struggling to separate my natural inclination to empathise with the student on their subpar performance. From this conversation we agreed that we should seek a third party to assess the pupils work, to avoid the possibility of confirmation bias[1].

[1] Steinke, P and P. Fitch, “Minimizing Bias When Assessing Student Work”, Research and Practice in Asessment. pp.88-95 < https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1168692.pdf > [Accessed 7 March 2024].

Evaluating and Analysing This Experience:

A negative aspect of this experience was the emotional toll it took on myself and Miss Hughes, as well as the student involved. Witnessing the student’s disappointment after falling short of their own expectations was disheartening. Moreover, the conflict I felt between personal connections and professional obligations lead me to feel stressed, with a hint of self-doubt, that I might be too lenient and crossing a boundary with my empathy for the candidates. This negative aspect highlighted the emotional complexity in education, as my desire to uplift and support the students must sometimes be tempered by the need for impartiality. On the other hand, a positive aspect of this experience was having a third-party assessor aid Miss Hughes and I with our marking, as they served as a safeguard that reminded us of the personal biases that arise from student-teacher rapport. The external examiner helped ensure that each student received a fair evaluation based solely on their final performance. Additionally, working alongside the assessor provided me with an opportunity of professional growth and development, by observing their neutral approach to the assessment and how they mitigated biases. This aspect of the experience was positive as it enhanced my understanding of assessment practices, whilst equipping me with valuable skills I can apply in my future teaching endeavours.

I recognise that my bias was an “inadvertent form”[1] and it stemmed from empathy and a desire to support the pupil through their disappointment. The student’s consciousness of their shortcomings amplified my desire to advocate for them to sustain their top band grade in the grading process. This aspect of my work experience in St. Malachy’s College did not go so well because of my empathy which ultimately made me question my examination integrity. However, I now understand the importance of managing and acknowledging biases within assessments. I am aware of how seeking external perspectives and maintaining professional integrity are crucial in ensuring fairness for both students and educators. This experience has underscored the complexities of teacher-student dynamics and highlighted the necessity of navigating them with objectivity and sensitivity.

[1] Kurdish Studies, “Achieving Assessment Equity and Fairness: Identifying and Eliminating Bias in Assessment Tools and Practices”, Vol. 11, No.2, p.4469. < https://kurdishstudies.net/menu-script/index.php/KS/article/view/1035/1085 > [Accessed 7 March].

Conclusion and Action Plan:

Ultimately, this experience was invaluable in my growth and journey to be an educator, as it forced me to confront inherent biases that could cloud my judgement. As well as, compelling me to approach the grading system with greater sensitivity, mindfulness, and an unwavering commitment to maintain the integrity of academic standards, regardless of the emotional challenges it may present. Through this challenge I developed a deeper appreciation for the intricacies of assessments within education and the responsibilities that come with it, something that cannot be learnt from a textbook but only by doing and being in an educational setting.

Finally, moving forward I am committed to implementing strategies to alleviate biases and uphold ethical standards in assessment. For example, seeking feedback from colleagues and external assessors to validate grading decisions.

Bibliography:

[1] The University of Edinburgh, “Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle”

[2] Steinke, P and P. Fitch, “Minimizing Bias When Assessing Student Work”, Research and Practice in Asessment. pp.88-95 < https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1168692.pdf > [Accessed 7 March 2024].

[3] Kurdish Studies, “Achieving Assessment Equity and Fairness: Identifying and Eliminating Bias in Assessment Tools and Practices”, Vol. 11, No.2, p.4469. < https://kurdishstudies.net/menu-script/index.php/KS/article/view/1035/1085 > [Accessed 7 March].