Introduction:

On an ordinary Wednesday of my placement at HUMAIN, I was engaging in my routine tasks as a Junior 3D Modeller.

Everything changed, once the following phrase; “WE HAVE ALLYSHEA”, was exclaimed and echoed into the main office, from the management space. Naturally, my internal panic started to creep in but I still tried to contain my external composure and emotions subtly.

The CEO approaches my desk and proceeds to explain the changes he intends to make for the company by creating their own inhouse studio for Motion Capture, or Mocap for short. He also mentioned his awareness of my current undergraduate studies in Drama, leading to the question that followed;

“Would you like to be our first ever actor in our cutting-edge Motion Capture system for Virtual Production?”.

This sparked a thrilling blend of nervous excitement within me to which without hesitation, I responded “Yes.”

I had to jump straight in without preparation or knowledge of how Motion Capture worked. This was an exciting and new learning opportunity for everyone involved.

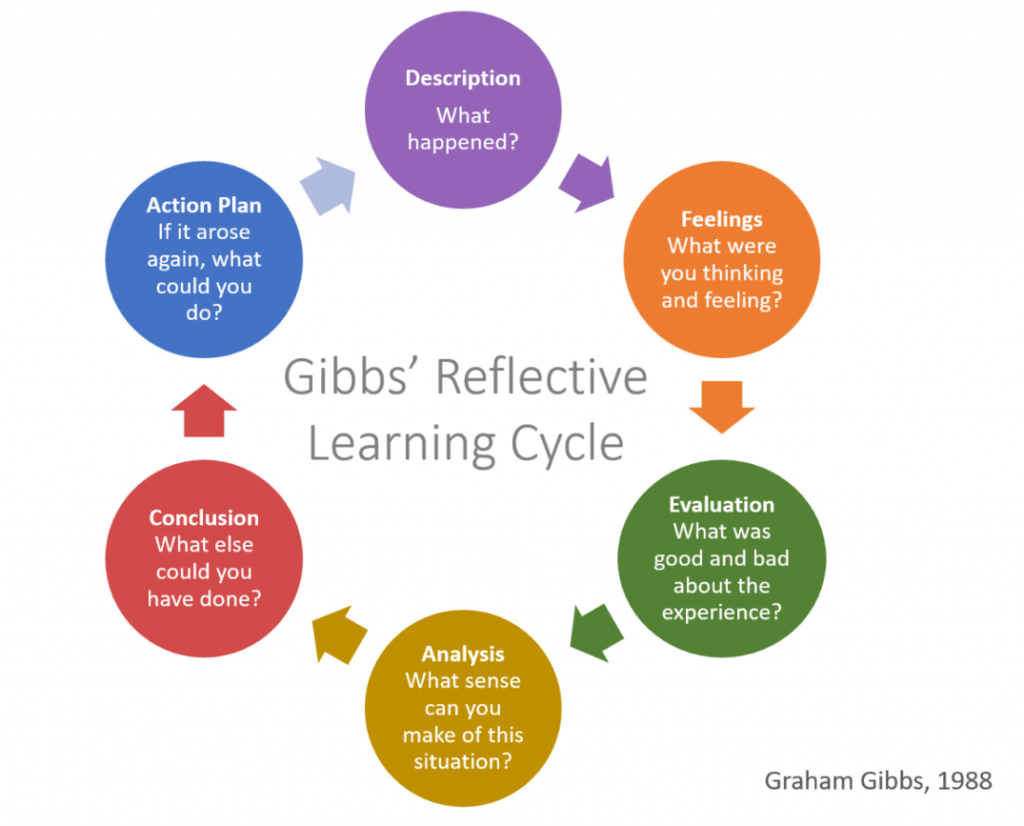

I will be using Gibbs Reflective Cycle (1988) to provide a clear description of the ‘Acting in Motion Capture for Virtual Production’ challenge, followed by an evaluation and analysis of what I discovered from that challenge. Finally, I will conclude this unique experience with professional and personal revelations with an action plan for future.

DESCRIPTION

“What happened?”

I entered the Motion Capture room where Robert, my R&D work colleague, marked dots on my face. This was essential for the production team to study my facial movements when expressing different emotions as the real-life actor. The dots will then be used as a reference in post-production, to the digital version of myself, replicating the exact facial movements.

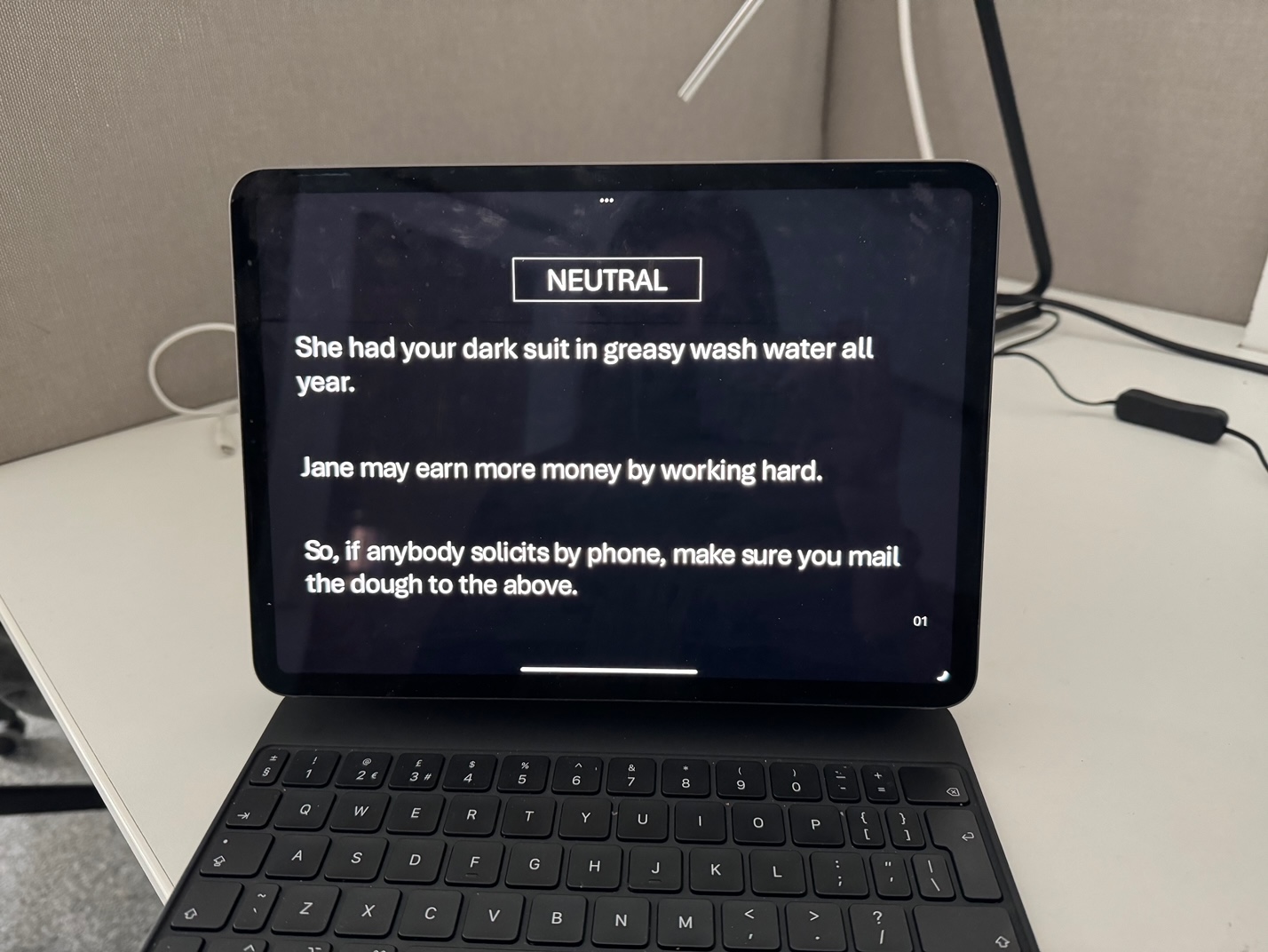

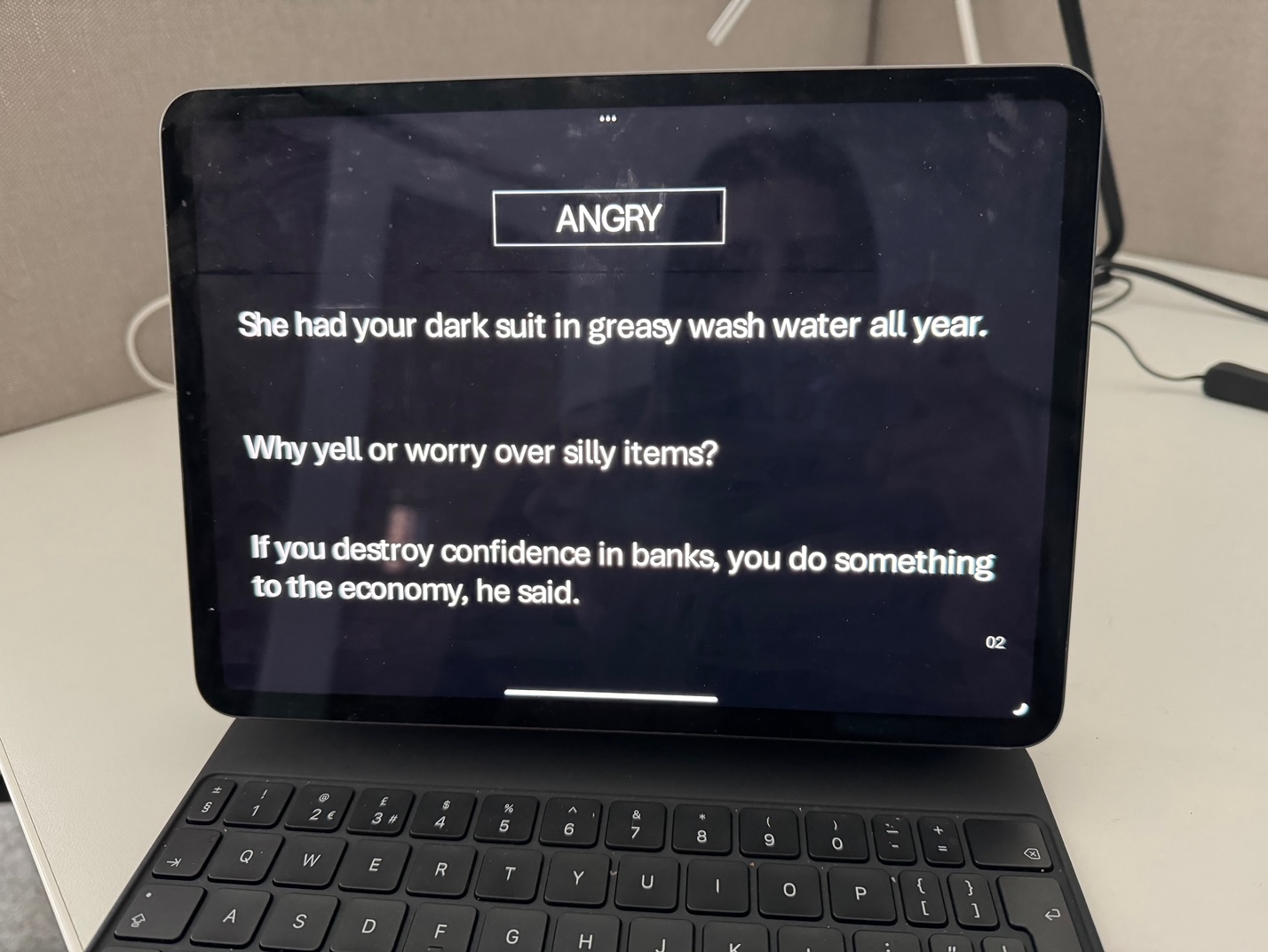

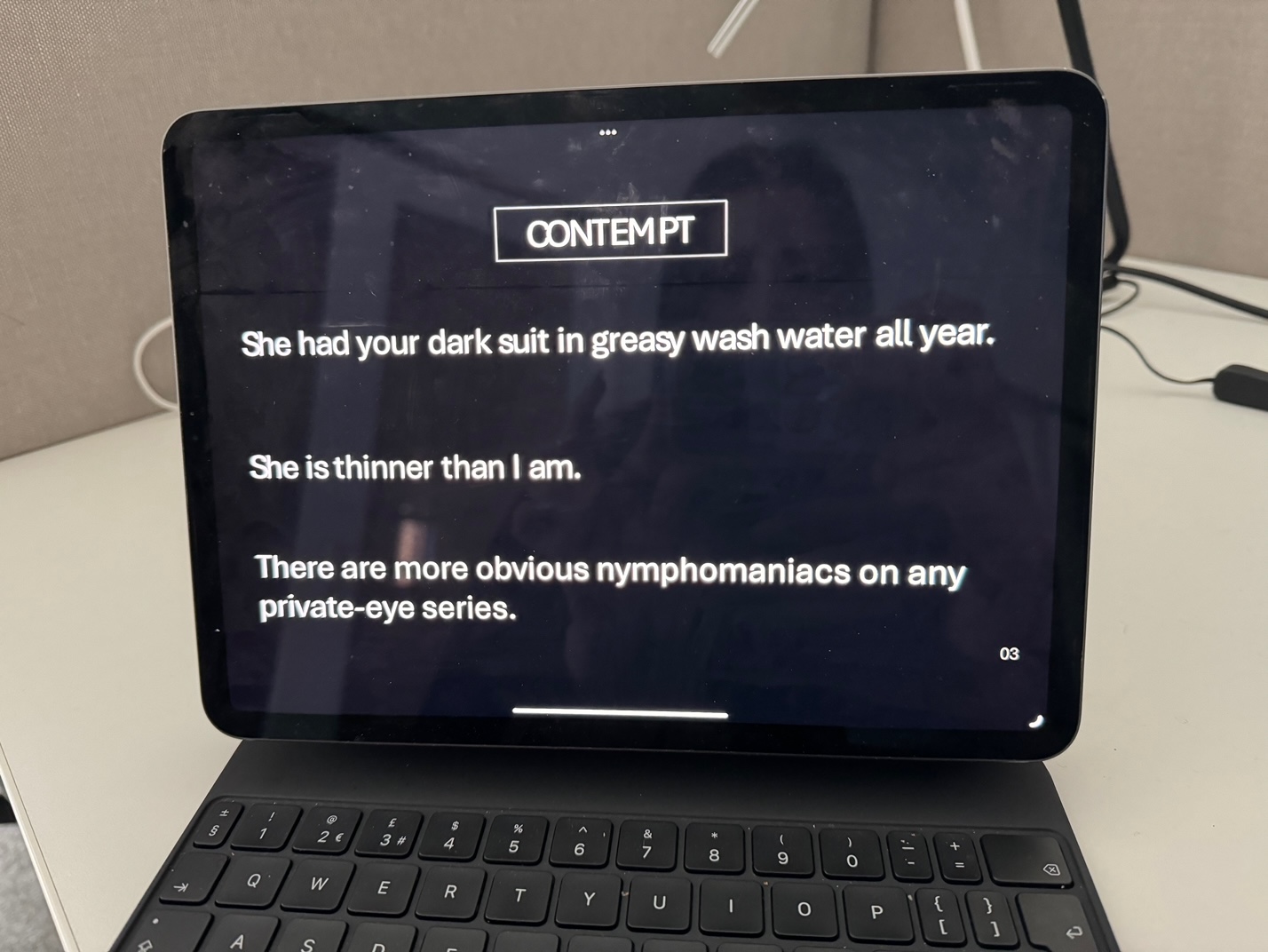

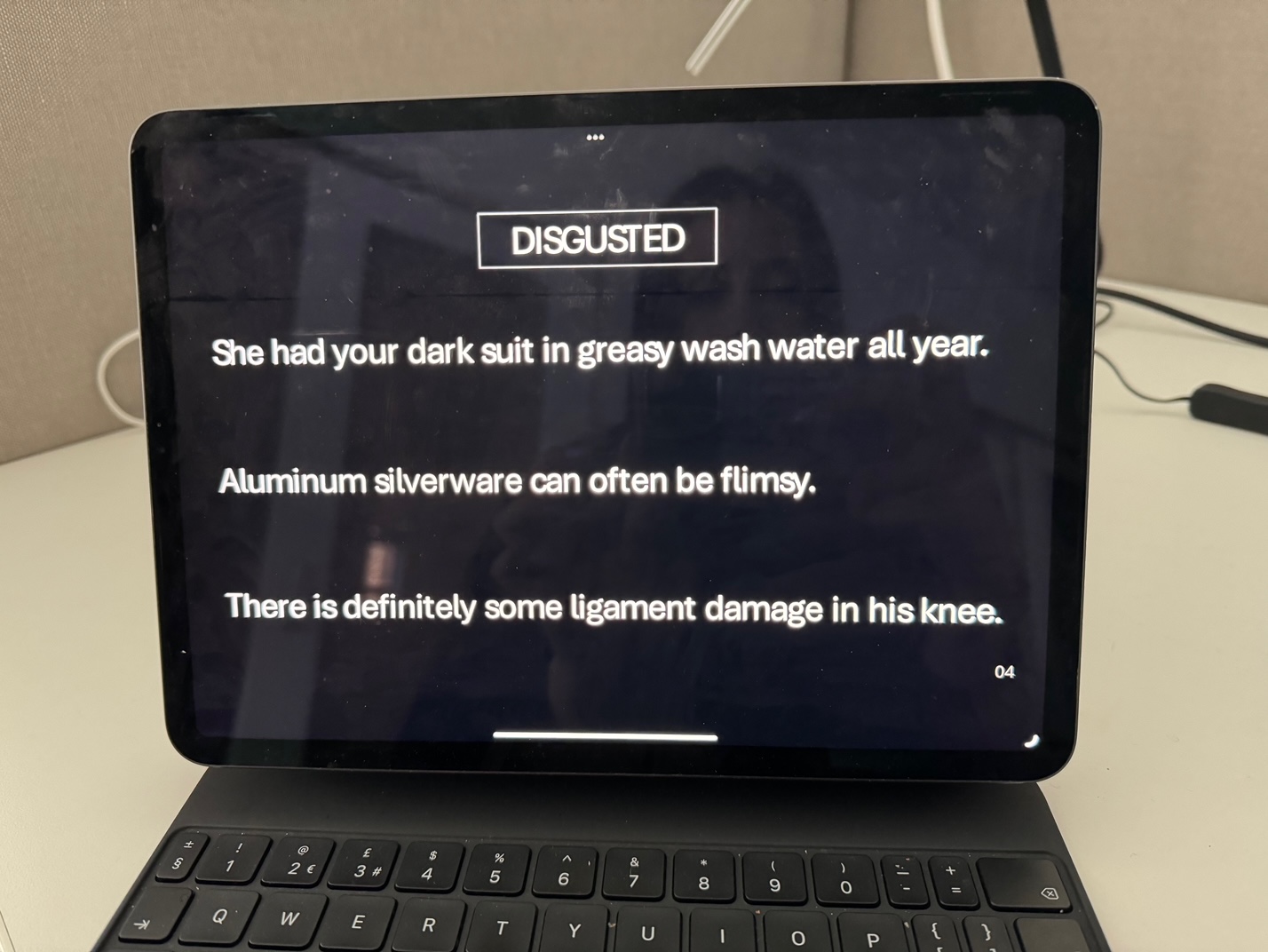

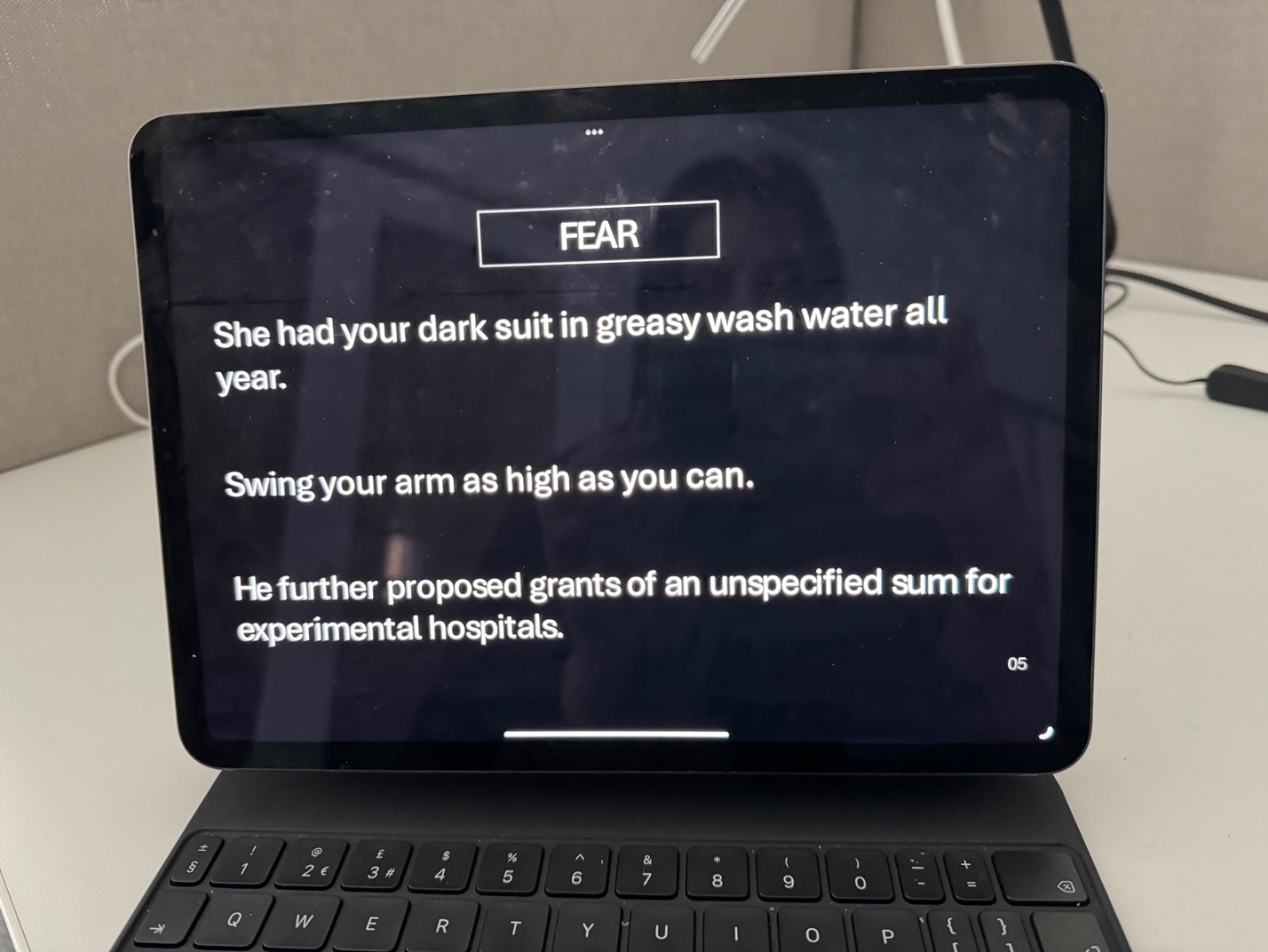

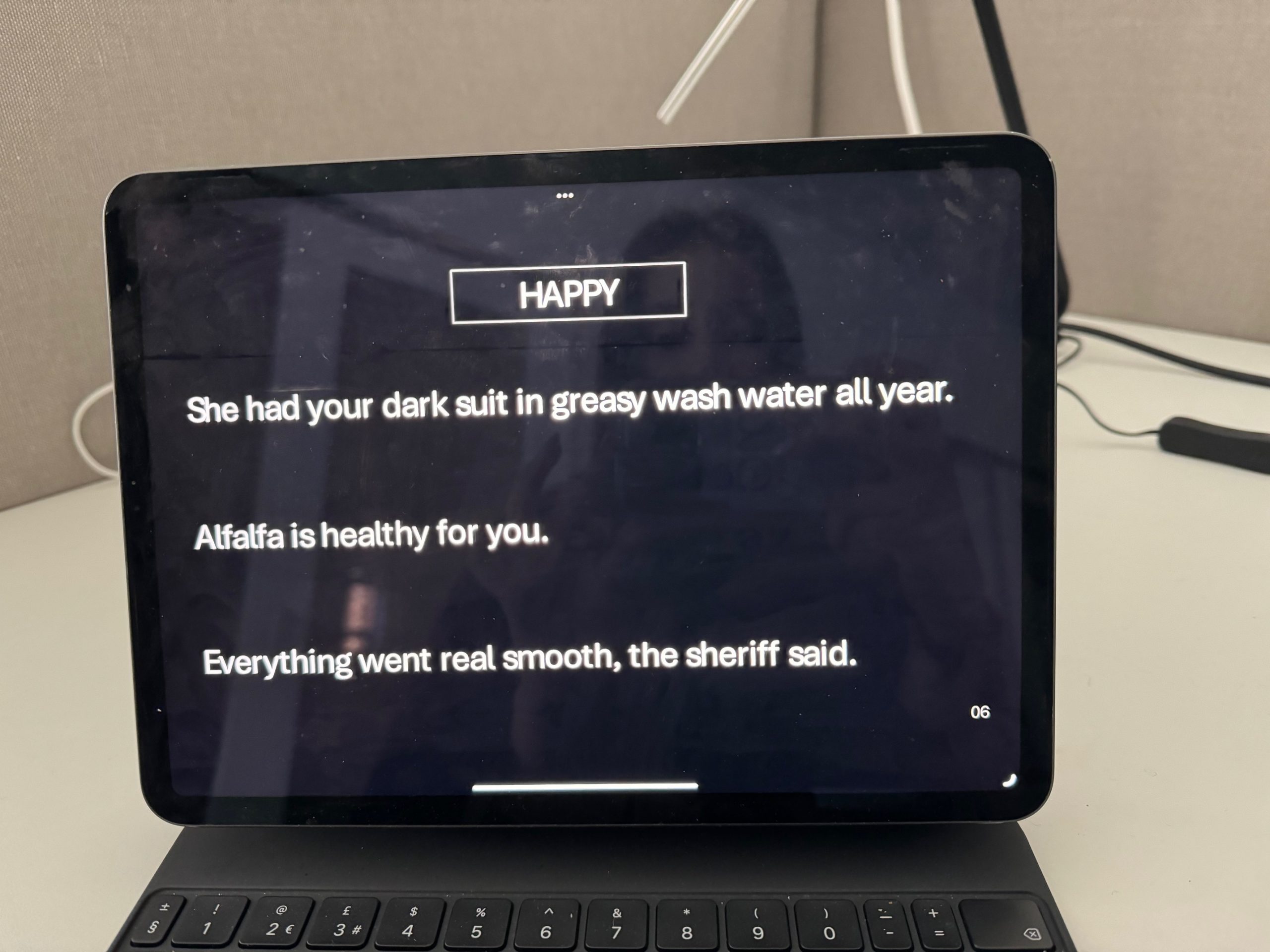

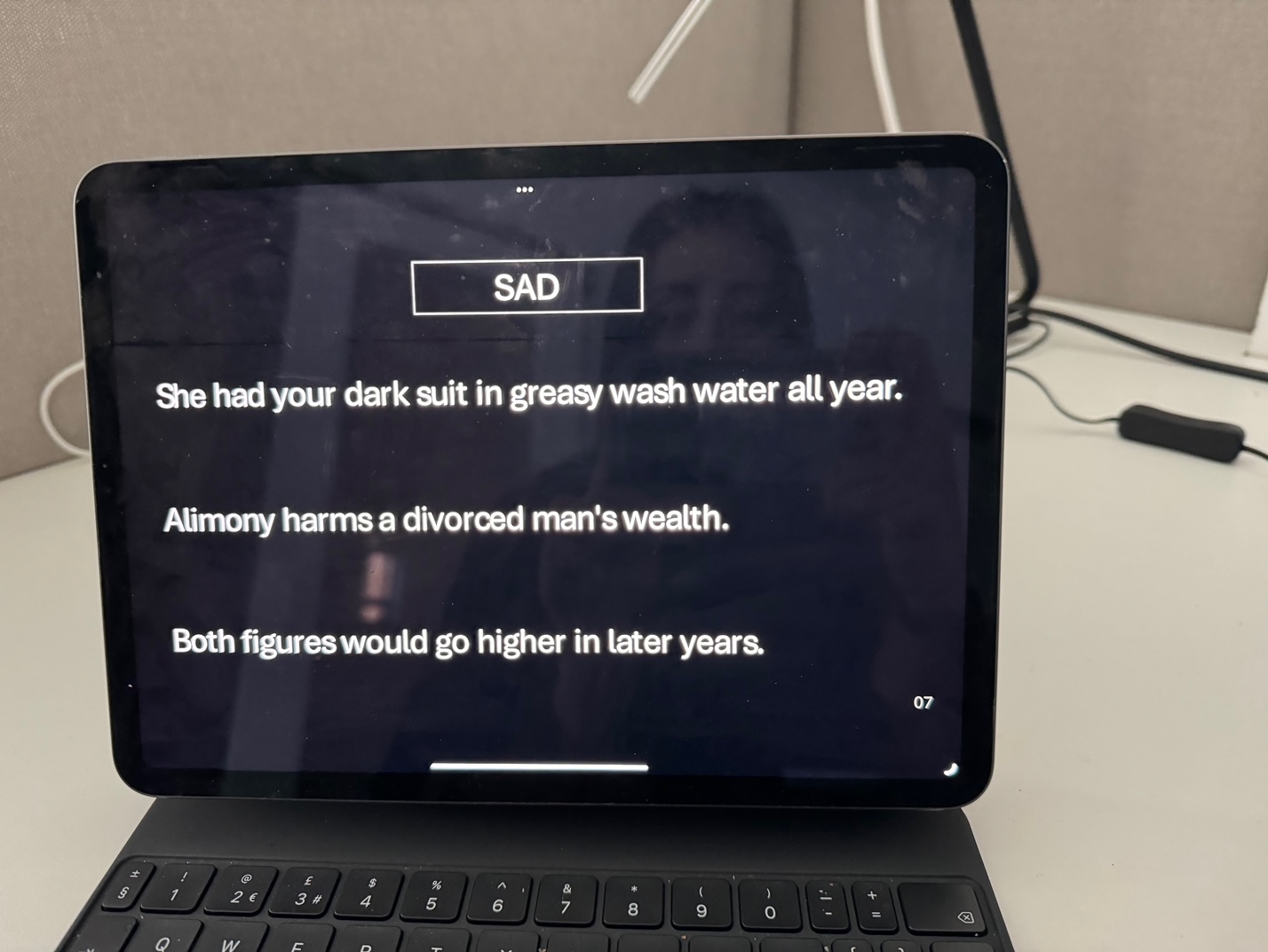

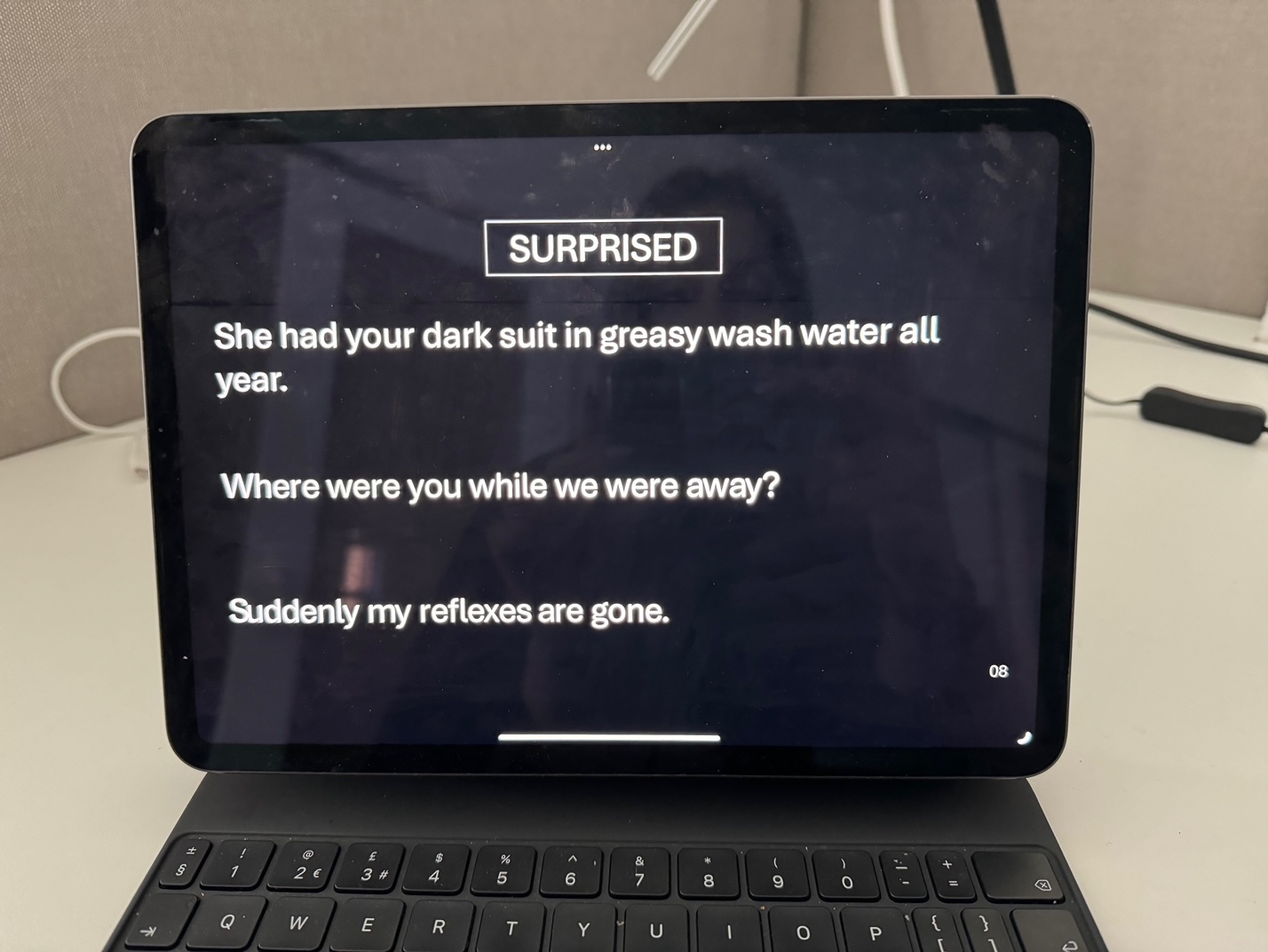

I was initially presented with 6 slides, as an example, of the type of emotions I’m expected to “perform” for the recordings. The task consisted of myself performing 3 different sentences from each slide in the requested emotion displayed above. I had to perform around 30 of these slides in total. The recordings took about a whole day’s work.

The emotions present in the slides were the following:

Neutral, Angry, Contempt, Disgusted, Fear, Happy, Sad & Surprised.

HUMAIN, Belfast. (Own Photos).

I was instructed to use a mirror to go over some of these emotions briefly and see how the dots moved around my face.

My work colleagues began to assemble the head equipment onto me for the Mocap. I had been given a microphone to speak into for the recordings and also had the slides in front of me to read off from.

FEELINGS

“What were you thinking and feeling?”

Thinking:

I was curious and intrigued with this technology and began to gather my previous memories of watching behind-the-scenes of actors undergoing Motion Capture for film and video game productions. I thought of the film Avatar and the Video Game The Last of Us.

Feeling:

I felt excited that I was given an amazing opportunity to witness first-hand what it would be like to act in a video game or film production where VFX and Animation are involved. I also felt a sense of relief that as my first time going into this, the only requirement was my facial acting. In comparison to actors from Avatar and The Last Of Us which required facial and full body Motion Capture.

Motion Capture Professional Images Examples:

EVALUATION

“What was good and bad about the experience?”

Good:

- My colleagues were very communicative and informative on the whole process. Whenever they would request me to do certain expressions, they would simultaneously explain what they were doing. This approach made me comfortable and I was aware of what I needed to do to assist.

- Since that day was marked as Day 1 of the experimental project, there was more room for mistakes to occur, the stakes weren’t as high even though we were still under time constraints to make it work.

- There had to be several takes of the performance of each slide, which provided flexibility on my part to try different approaches in performing improvisation.

BAD:

- 20-30 minutes into the recordings, the head equipment started to feel heavy and tight. My concentration with performing was often clashed with the discomfort and tiredness.

- The camera attached to the head equipment was heating up since it was working wirelessly in real-time. The heat was getting more and more sensitive towards my face.

- The project took about a whole day, therefore I was not able to remove the markings off my face, which also meant I could not leave the office during breaks.

ANALYSIS

The Challenges of Intimate Close-up Facial Recordings

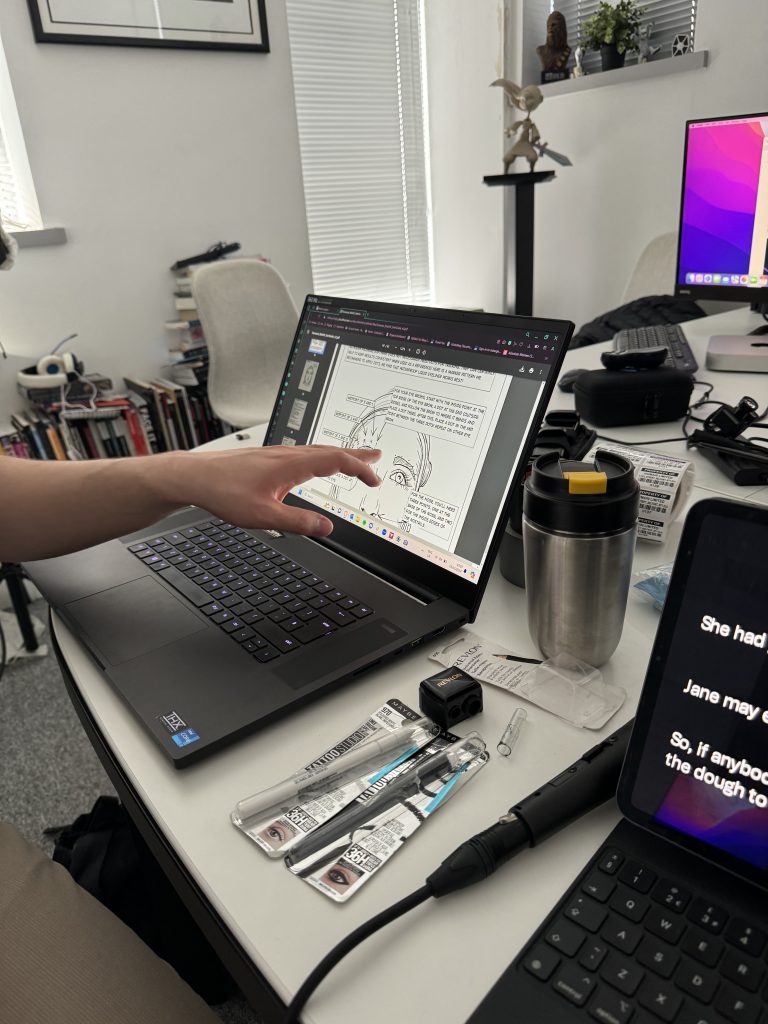

While performing the first couple slides, I had no access to the recordings of my performances. I was only able to access it after the team was critiquing the shots.

This was where I encountered an inner self crisis. I was aware of how I looked like as a human generally, but because it was such an intimate close-up, recorded from a birds-eye view, I felt shocked, embarrassed and exposed. This was quite a different perspective of watching back into my performance.

This is an example, slightly exaggerated, of what I saw when reviewing my previous recordings. It is evident how intimate the shots are, highlighting every little detail of the actor’s face.

Despite my incremental inner crisis, I diverted my attention towards understanding how this fits within the whole production. I discovered that the intimate close-up is necessary to understand the details of the actor’s face for the virtual production. While the angles are awkward, these types of close-ups will not be present in the actual video game or film but that it contributes to the makings of realism of the emotions displayed in the virtual characters.

Imagination Restrictions for Improvised Acting in MOCAP

Recalling the performing-based modules in my current undergraduate degree in Drama, when improvising as a solo performer, the actor uses imagination on establishing a setting and an “imaginary” scene partner. In fact, without imagination, the actor is powerless in animating a play-text or script.

This was a challenge I encountered while improvising the sentences provided, as most of the sentences lacked the possibility of imagination and sense.

Examples from slides:

“There are more obvious nymphomaniacs on any private-eye series.”

“So, if anybody solicits by phone, make sure you mail the dough to the above.”

Through my independent research and analysis of this topic, actors do often have to face poor acting conditions in Mocap performances. Unlike in the theatre stage where there is an on-going sense of structure in the story, in the Motion Capture recordings, there are disconnected scenes in which actors have to use their improvisation skills to make it appear as natural and effective to the contexts.

CONCLUSION

“What have I learnt?”

- I gained an understanding of how Mocap works for actors and the production team. The importance of both parties communicating effectively can allow for great results. This experience enlightened me with the very basic foundations needed for Mocap performing.

- The dots marked on my face were in relation to the muscle groups responsible for the temporary movements that occur in the facial appearance when “performing” emotions. This made me aware of how my face works and has enabled me to learn more about facial anatomy further.

“What skills have I developed?”

- Learning to improvise using solely facial expressions, without incorporating body and head movements.

- More insight into the facial bone, muscle structures and the way they move when certain emotions start to form.

- Patience and perseverance when approaching a project in experimentation.

- The ability to adapt quickly to new methods, allowing myself to be flexible and versatile.

- Develop an ‘eager to learn’ and open-minded mentality.

- Gaining comfort in seeing myself through intimate close-up shots when performing.

“How will this benefit my degree and future career?“

- This contributes towards my university career not only as a performer but also as a director, with increased awareness of the importance of imagination and understanding of the expressive human face when delivering performances.

- This also benefits my future career aspirations as a 3D Modeler & Animator; through understanding an actor’s approach of producing emotions and implementing that craft to the virtual makings of the animated character. In addition, learning more about facial anatomy contributes to the realism and effectiveness of bringing out the emotional side of the character.

Successful End Of Day Photo:

ACTION PLAN

If this opportunity arose again and if I had time to prepare for it, I would explore more into the art of imagination for improvised performance. This is a necessary skill not just for actors, but also for aspiring 3D Animators as both are responsible for breathing life into a character. The only difference between the 2 professions is that the Animator is required to do that from an objective point of view.

Another skill I would look into developing more is in regards to the connections of human anatomy and emotional expressivity. This is another beneficial skill for Actors and Animators. The ability to detect what happens in the face and body from an emotional trigger, would allow for a more effective approach when animating the details in the virtual character. This would allow for the audience to relate, empathize and be more perceptive towards the digital characters.

Bibliography:

R. K. Kammerlander, A. Pereira and S. Alexanderson, “Using Virtual Reality to Support Acting in Motion Capture with Differently Scaled Characters,” 2021 IEEE Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Lisboa, Portugal, 2021, pp. 402-410, doi: 10.1109/VR50410.2021.00063. Accessed 6 March 2024.

Turner, Craig. “Dreaming the Role: Acting and the Structure of Imagination.” Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, vol. 7, no. 4 (28), 1996, pp. 16–29. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43308266. Accessed 6 Mar. 2024.

MacMillan, K and Weyers, J. (2013) “How to Improve your Critical Thinking & Reflective Skills“, Harlow: Pearson Education UK.