Live sound is a catch-all term that covers a huge variety of applications; from operas to open mic nights, ballets to ‘battle of the bands’, the job of a live sound engineer is always hands-on, and it’s always been the practical, rather than the purely theoretical, that I’ve found most interesting. My course has always been largely theory based, so naturally I was both excited and a little apprehensive when I made my mind up to find a placement working on live sound – how similar was this going to be to the limited experience I had in the area? Was what I had learnt on my course going to prove at all useful? Just how adept were they expecting a third-year audio engineering student to be? After considerable scouring of opportunities in the Belfast area, I managed to secure separate placements with two organisations: the ‘Belfast Ensemble’, a local and quite prestigious touring theatre company, and ‘Accidental Theatre’, a nearby venue which plays host to a wide variety of performance-based events.

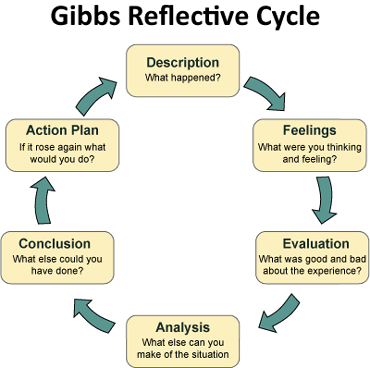

In this, my first reflective blog, I’m going to reflect upon my first, and indeed a fairly typical, day of placement at Accidental Theatre using Gibb’s reflective cycle, a cyclical method for introspection and self-improvement developed by Graham Gibbs.

With a view to clocking up the hours, I set to work, first spending an afternoon and evening at Accidental Theatre. There I met Marty, the venue’s sound engineer, who I had been in contact with via email. Marty showed me around the venue – straight off the bat this was a humbling experience; although Accidental Theatre is not a huge venue, the equipment they use is industry-standard and was a far cry from the amateur kit I use at home. I immediately felt quite out of my depth, and tried to bear in mind that this was fairly normal for a first day on any job. Having explored some of the books in the AEL3001 recommended reading list I was reminded of a quote from the book: ‘Beginning Reflective Practice’ by Melanie Jasper, that pointed out that, when in such situations, it was important to remember that I was ‘primarily a student, placed in practice for the specific purpose of learning from that environment’[1]; I steeled myself and cracked on.

A Description of the experience

The day consisted of shadowing Marty and helping where possible. The theatre was hosting an experimental music event that evening, so our first task was to set up and test the equipment. Multiple acts were scheduled across multiple floors, with video and audio feeds being mixed separately and sent to staff in the basement for live stream broadcasts. This was achieved, after considerable fiddling and fettling by implementing DVS (Dante Virtual Soundcard), a software application for patching and sharing media streams between local devices which Marty said is commonly used in big venues such as theatres. The acts were diverse in nature and their respective requirements – the first act was a solo drummer who only needed two microphones, the second a duo from the QUB ensemble who performed using electronic instruments and vocals, and the third was a solo artist who played a synthesiser through several effects pedals and cassette recorders to create a rich soundscape. Each performance had to be carefully mixed for clarity and cohesiveness both in the room and on the outgoing live streams. During this process I was shadowing Marty, watching carefully and absorbing as much as possible as he moved between floors and performances, working between two Behringer X32 mixers and their virtual counterparts on an iPad.

At some points, whilst he was taking care of the audio feed for the stream, Marty allowed me to operate the iPad and mix the sound in the room. This represented a big step for me; there were a lot of people in the audience, and the nature of experimental music meant that the dynamic range of each performance was quite large and therefore constant adjustments to levels were required. I was rather pleased and relieved that, under my watchful ear, no glaring errors were made.

Feelings and thoughts of the experience

The experience was quite unlike anything I’ve done before and gave me a great insight into the role of a sound engineer. Initially I felt quite overwhelmed by the sheer volume of equipment being used, and how alien it was to me – I’d rather naively hoped that my casual experience of setting up equipment and mixing mine and my friend’s performances at home would be a good head start on the job. Unfortunately, this wasn’t the case and at times it was hard to subdue the feeling that perhaps I was a burden to Marty, hindering his concentration and therefore the finished sonic product with incessant questions. I expressed this to Marty, who was very understanding and assured me that, even after several years in the role, he still didn’t feel as though he knew it all – he was more than happy to field any questions and did a great job of explaining (not always in layman’s terms) what he was doing.

I think the decision to voice these feelings, rather than suppress them, came from reading some of ‘Reflection, turning experience into learning’ [2], specifically the chapter entitled ‘Reflection and Learning: The Importance of a Listener’, written by Susan Knights. Knights, an adult learning consultant, argues that “in the learning situation, reflection is most profound when it is done aloud with the aware attention of another person”.

An Evaluation of the Experience

Overall, the experience was very positive and presented me with a great opportunity to learn. I was reliably informed that the only way to get comfortable and develop skills in the area is to spend time working in the area, therefore any relevant experience, whether positive or negative, is useful experience. Knowing how to efficiently operate a piece of kit is invaluable in a dynamic live environment, so I felt very fortunate to be shown the ropes by someone who has been in the job for some time. It’s hard to pinpoint any aspect of the experience that isn’t beneficial in some respect – even when I felt uncomfortable or out of place, I was learning something.

An Analysis of the Experience

I think what made the experience wholly positive rather than entirely negative and soul-crushingly humbling was accepting that the steep learning curve of the role was unavoidable, and that it would take time to become more comfortable and eventually maybe even useful. Having discussed my initial nervousness with Marty, I came to realise that being a bit kinder to myself allowed me to ask questions that were maybe more naïve but were also more beneficial to my learning, as they allowed me to build more fundamental knowledge.

Conclusion and Aims

Through talking to Marty and watching him work, I was able to learn a lot about the day-to-day role of a live sound engineer; one thing that surprised me is how diverse a performer’s requirements can be, even within one single evening. A useful piece of advice from Marty was that working in live sound is often an exercise in compromise – conditions are rarely perfect, and things often go wrong, so it’s important to be prepared. Knowing your equipment inside out is invaluable; A venue’s live sound is controlled using a sound desk – there’s no one desk to rule them all and there are multiple options across multiple price ranges, so different venues have different desks. Working with Marty at Accidental theatre gave me hands-on experience with the Behringer X32, and by asking lots (and lots) of questions, I was able to learn the basics of that specific desk and how any desk might generally be used in live sound applications; there are many techniques for routing and manipulating sound that are used almost universally.

Action Plan for the future

In situations such as these, I think it’s vital to identify and make the most of learning opportunities, both as they present themselves and in retrospect. In her book, ‘Beginning reflective practice’, Jasper says ‘In a way, reflective practice is a shortcut to learning. You will learn more quickly if you get into the habit of reflecting on your experiences’ [1].

In future I will improve my approach to learning by continuing to implement reflective practice, and I will also use the knowledge I am accruing to ask more informed and articulate questions thereby getting to the core of what I need to know more efficiently. I am going to ask Marty to show me more about the live streaming aspect of the job. I think this is a very useful thing to know about – since the covid pandemic and resulting lockdown, live streaming of performances has become hugely popular, and people with knowledge and experience in the area are highly sought after.

References

[1] Jasper. (2013). Beginning Reflective Practice.

[2] Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (Eds.). (1985). Reflection, turning experience into learning. Kogan Page.