From the 30th to the 31st of May this year, the International Society for Heresy Studies held its inaugural conference in New York University, bringing together researchers of heresy from all disciplines and periods. Identifying a ‘return to religion’ in the work of cultural critics and philosophers, the Call for Papers sought to attract presentations that would contribute to the complication of terms used in discussions of religion which are, more often than not, left unproblematised. With an inherent emphasis towards interdisciplinarity, the CfP encouraged applicants working in literary history, philosophy, sociology and theology, among others, to contribute to their discussion of heresy.

As soon as the CfP hit my inbox (thanks to my tireless (and hawk-eyed) supervisor), I jumped at the chance: the material I was preparing for Differentiation was centred around exploring how critics understand religion in the Middle Ages, attempting to unpack the meaning behind ‘religion’, ‘heresy’, ‘orthodoxy’ and ‘belief’. I submitted a proposal for a paper, and a few months later, thanks to AHRC funding, I found myself on a flight to NYC! (Not too shabby for my first international trip!) The conference began with a General Membership Meeting, in which the meanings behind the terms which would be the focus of the conference – ‘heresy’, ‘Christianity’, ‘God’ – were explored, unpacked and problematised. As with any exploration and complication of issues and terms, more questions than answers arose, setting up a stimulating few days of papers and discussions.

As there were so many diverse and interesting papers, the conference itself was structured with parallel sessions; thus, the Medieval Heresies session was one of the first panels to run concurrently with sessions on the History of Heresy and 17th-Century Heresy in England. Luckily (or, more likely, due to subtle selection of proposals), all three papers in my panel related to each other in interesting and unsuspected ways. I gave a paper entitled ‘The Politics of Naming “Heresy”: Unbelief and the “Age of Faith”’, exploring and problematising the terms one traditionally uses to describe heresy in fifteenth-century England. Kathryn Green, from the University of Louisville, presented a paper entitled ‘The Joys of Heresy: Benefits for Women in Medieval Heretical Sects’, exploring the ways in which medieval heresy – Lollardy in particular – may have offered a less oppressive life for women than orthodoxy. The final paper was from Julie Gaffney, from the City University of New York, entitled ‘Weeds and Words: Interpellating Heretics, Name-calling, and Lollard Poetics in Chaucer and Langland’, a paper which also explored heresy in Mum and the Sothsegger. The discussion which arose in the question and answer session was stimulating, focusing mainly on working out how we define ‘orthodoxy’ and ‘heterodoxy’, with all papers linking into one another in quite useful and interesting ways.

The conference proceeded with many papers and panels attempting to tease out more complex and nuanced ways of using the terms which seem to come naturally to us when we talk about religion; when it comes to thinking about the meaning behind such terms, however, our accepted truths, our unquestioned ‘facts’, start to crumble, revealing much more interesting areas of investigation. Three plenary talks were included in the programme for the conference: James Wood, Professor of the Practice of Literary Criticism at Harvard University, delivered a paper entitled ‘Belief, Disbelief and the Modern Novel’; Rebecca Newberger Goldstein, novelist and philosopher, delivered the second plenary talk entitled ‘The Accidental Literary Influence of Modernity’s Greatest Heresy’; and Thomas J. J. Altizer delivered the final plenary talk entitled ‘The Absolute Heterodoxy of William Blake’.

The roundtable, facilitated by Robert Royalty, Jr, James Morrow, Rebecca Goldstein, Gregory Erickson and Edward Simon, used the term ‘heresy’ itself in a variety of ways, both talking about historical heresies and personal heresies, seeming always to define it as a rebellion against a certain authority. As with any spontaneous discussion, occasionally self-contradicting statements were made and definitions became less, well, definitive, which nevertheless indicated the fruitful and exciting new means of exploring what heresy could mean in 21st-century scholarship. The ISHS is now accepting submissions for its newly founded journal; the link to their website can be accessed here.

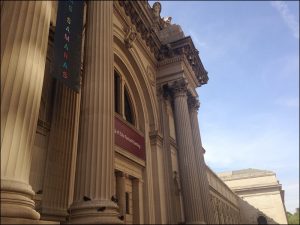

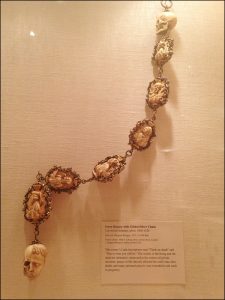

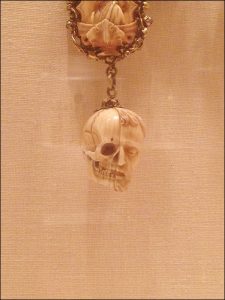

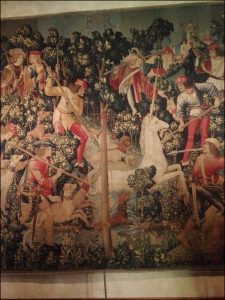

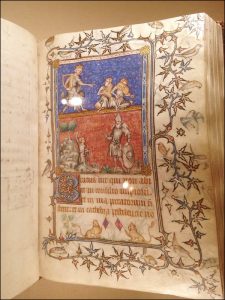

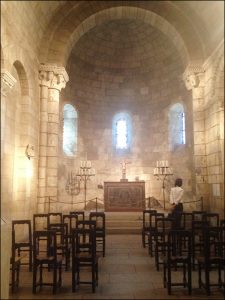

Of course, no visit to New York would be complete for a medievalist without a trip to the Metropolitan Museum and the Cloisters! Although my trip was brief, I managed to go see both; below are a few pictures of some of the beautiful artefacts on display.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Ivory Rosary Beads, German, c. 1500-1525

Hanging Lamp, Italian, c. 1350-1400

Close Helmet with Mask Visor, German, c. 1530

The view from the beautiful roof garden

The Cloisters, New York

One of seven unicorn tapestries held in the Cloisters

The Psalter and Hours of Bonne of Luxembourg, Duchess of Normandy, French, before 1349